Smart bike share technology and funding policies help bridge the transit gap through the final mile as Andrew Bardin Williams explains.

The sharing economy is coming to Portland this summer. BikeTown, the city’s new bike share program sponsored by Nike, will be launched in mid-July with 1,000 bicycles distributed across 100 stations throughout the city. Originally funded by a $2 million federal grant, the program has been boosted by a $10 million sponsorship deal with Nike ensures funding for the next five years and has allowed the city to immediately expand the fleet by 66%.

As the demand for bike share grows in the US, cities are having to come up with new ways to not only initially cover the capital costs of the programs but also ensure that on-going maintenance, replacement and expansion is properly funded for the long-term. Bike share proponents have opened up three fronts to ensure the long-term viability of bike share in the US: investing in smart bike solutions that make bike share efficient, safe and convenient for riders; recruiting title sponsors such as Nike in Portland; and opening up dedicated bike share funding sources through legislation in Congress.

Meanwhile, BikeTown represents the 66th bike share program in the US (The Bike Sharing Blog keeps a running tally on its website), including 22 new systems in 2015 alone. This growth is proof that transportation planners now see bike share as a critical component of a multi-modal transportation system and a way to bridge the public transit gap through the final mile. Always a challenge for US transportation systems that have traditionally been dependent on the automobile, the last mile represents the tipping point for local agencies between people embracing public transit and falling back on the convenience of single-occupancy vehicles.

“The US has always been missing the seamless interconnected transportation networks that people in Europe take for granted,” said Tim Blumenthal, director of the advocacy group People for Bikes. “We need to make the whole ride safe and appealing, and people are realising that bike share can fill that need.”

Multi-modal

Aside from a few idealistic efforts in the 1960s, bike share was virtually non-existent in the US until recently. The first modern program was temporary, set up by bike evangelists during the 2008 Democratic National Convention (DNC) in Denver. More than 1,000 bicycles were made available to delegates, media and other members of the public throughout the weekend, showing that bike share could be a quick and relatively inexpensive way to get people ‘from A to B. Labelled a success, a permanent bike share system was put in place in Denver two years later using automated solutions to help reserve, unlock and reallocate the bikes around town.

Since then, bike share has exploded in the US and is seen as a critical component of a multi-modal transportation system - providing choice for residents and visitors. According to Blumenthal, Americans are moving and working in more urban areas as part of a desire to drive less. As a result, travel patterns are changing from the 20th Century’s hub and spoke model to more flexible migration patterns where people travel across town or do reverse commutes where they live downtown and work in the outer neighborhoods or the suburbs. And while American public transit has made huge strides in the past 20 years, the fixed transit infrastructure to support these changing transportation patterns is not there yet. City planners are hoping that bike share can provide a more flexible transit layer to fit these changing needs.

“As bike share technology matures, you’re going to see it become more of a part of a city’s transportation network with interconnected plane, rail, light rail, bus and bike systems all working together,” said Bob Burns, president of BCycle, a bike sharing company formed out of the DNC trial in Denver and one of two major US bike share vendors.

According to Burns, cities are flocking to bike share as a way to reduce congestion and parking bottlenecks while contributing to healthy, vibrant cities by encouraging exercise and reducing pollution and carbon emissions. City planners are using bike share as a form of social equity, giving low-income residents access to high-quality bicycles. Often bike share memberships are subsidised or free and some cities even offer the first 30 minutes of every ride free.

Innovative funding

However, despite the inherent benefits of bike share, funding continues to be a problem. Capital costs to get a program up and running can bleed into the millions of dollars even for small city deployments. There’s equipment to purchase, ridership studies to finance and marketing campaigns to run. However, bike share is relatively inexpensive and quick to set up compared to fixed transit which can run into the tens or hundreds of million dollars and take years to build.

“The compared costs are few, but bike share programs can still be daunting financially for a city,” Blumenthal said. “You’re talking about a transportation system that needs to move thousands of people every day—often one way. It takes money to launch, manage and promote.”

According to Blumenthal, bike share in the US is funded by six sources: users; advertising; sponsorships; and city, state and federal grants. However, Congressional funding earmarked for general transportation projects are not eligible to be used for bike share programs. But it may not be that way for long.

In January Representatives Earl Blumenauer (D-OR) and Vern Buchanan (R-FL), co-chairs of the Congressional Bike Caucus introduced the Bikeshare Transit Act (H.R. 4343) - bipartisan legislation that will provide local communities additional flexibility to use federal funds for bike share programs. The legislation clarifies that bike share projects are eligible for existing federal funding and defines bike share in federal transportation law, giving much-needed certainty to commuters, business owners and city and local officials.

“America is in the middle of a bike share revolution. Removing barriers faced by new and existing bike share programs is important to providing choice and adding value to our existing transportation network,” said Representative Blumenauer in a press statement.

The simple fact that a Congressional Bike Caucus exists is proof that bike share has the support of government officials.

Powerful Technology

ITS technology is also making bike share a more viable transportation mode that is cost efficient for transit agencies and safe and convenient for riders. The trend has been to migrate the technology away from docks to the bikes themselves. Best practices require two docks for every bike, meaning that bike share organisations can halve the amount of technology they need by shifting the ‘brains’ to the bicycles.

Two bike share vendors dominate the US Market:

BCycle

Business Model: Partners with local transit agency or non-profit in mid-size cities

9,000+ bicycles in operation

1,100+ stations

3.8 million trips

41 U.S. cities

Motivate

Business Model: Serves operator in big cities

20,000+ bicycles in operation

1,800+ stations

18 million trips in 2015

10 U.S. cities

Portland is outsourcing the operations of NikeTown to Motivate, the other major bike share company in addition to BCycle, in an effort to be more efficient and to keep up with rapidly changing bike share technology. Motivate is building a central control centre in Portland where 10 employees (including mechanics, IT technicians, marketing and customer service) will maintain the day-to-day operations of the program. According to Dani Simons, director of corporate communications for Motivate, higher than expected ridership numbers may require additional staff. The program’s software backend and the Nike-branded bikes are manufactured by Brooklyn-based Social Bicycles.

Portland bike share users can reserve a bicycle online, through a mobile app or in person at a kiosk. Users simply wave an RFID dongle over the bike and it automatically unlocks from the dock. While in use, a GPS unit in the bike pings off a satellite every five to 10 seconds, sending critical data to the bike share backend that can be analysed in real time. Algorithms use the information to make rebalancing recommendations (since most bike share trips are one-way, bikes often have to be picked up and redistributed to docks around the city) and build rider profiles that help streamline the overall system. Behavioural differences between commuters versus casual riders, men versus women and residents versus tourists can be tracked and used to make the system more efficient and convenient.

The mobile app also allows riders to find an open dock near their destination in real time. If none are available, users can park the bike at existing, non-bike share racks around the city for a $1 rebalancing charge. However, if another user in the area picks up the bike, then the fee is refunded—giving users an incentive to help with rebalancing.

Otherwise, Motivate employees will reposition the bikes manually—either by trailer or by pedalling the bikes to a new location. Valet stations could also be set up at peak demand areas. Data analytics will be key in the first few months of deployment, allowing Motivate to collect pertinent data that can be used to streamline rebalancing further. Simons says that there are plans to gamify rebalancing in the future.

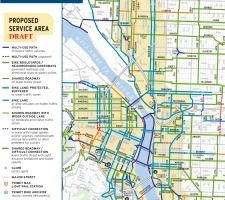

Scheduled for a July launch, BikeTown is currently in the planning stages, finalising the service area and determining where to position the 100 stations within that area.

According to Steve Hoyt-McBeth, the City of Portland manager for BikeTown, a team is analysing best practices gathered from other bike share programs in the US as well as Portland-specific factors such as density, zoning, walkability and existing bike lane networks. “It’s important,” says Hoyt-McBeth, “that the final decisions adhere to the city’s policy goals—such as expanding accessibility to and from affordable housing.”

Public-Private Partnership

The Nike title sponsorship deal allows Portland to achieve many of its goals. The original plan was to launch with 600 bikes—a figure that ballooned to 1,000 with the additional funding—and BikeTown will benefit from the marketing expertise from one of the world’s most recognizable brands.“There are 600,000 people in Portland. Maybe 1,000 have heard of bike share, but 599,000 have heard of Nike,” Hoyt-McBeth said. “The sponsorship allows us to reach more people and bring new people to bicycling.”

Other cities have title sponsors too - Citibank in New York, Independence Blue Cross in Philadelphia and Kaiser Permanente in Denver—and Blumenthal expects more cities to follow suit to help them bridge the funding gap and grow quicker with a more steady long-term financial footing.

New funding options, federal legislation and smart ITS solutions make bike share a vital component of a connected city and is here to stay.

- About the Author: Andrew Bardin Williams is a freelancer journalist and US Contributing Editor for ITS International