Total Transport is a concept that is gaining traction in Europe as a means of making it easier for people without access to a car and living in rural and remote communities, to travel to work, the shops, schools and hospitals. It involves maximising vehicle availability and integrating scheduled services with other transport services (including taxis) commissioned or contracted by more than one local government agency and delivered by more than one operator.

The argument is that better coordination and pooling of resources and expertise that are already available through regular, dial-a-ride and user-specific services (the latter including school and hospital transport) can bring worthwhile benefits in cost reduction and user convenience. Not least because more attractive and convenient travel options for the public can encourage lower car use overall.

The Netherlands has been encouraging such schemes through its 2015 Social Support Act (WMO), which commits local governments to managing the full integration into society of ‘people with limitations’. This includes meeting their transport needs by, for example, negotiating contracts with external providers.

One of these, Bios ZCN Totaalvervoer, delivers trip combinations using existing operators via a central despatching system (called regiecentrale). Another, Texelhopper, has replaced scheduled bus services on the island of Texel (north of Amsterdam) with combinations of on-demand buses and taxis, using integrated payment. Taxis can operate as buses and carry people with disabilities who are unable to use conventional public transport. Travellers can book online.

In other areas, integrated taxi services known as

In the UK, regional and local public sector agencies spend around £2bn (US$2.6bn) annually on transport, the most important beneficiaries being school buses (£1bn, US$1.3bn), support for local bus services (£350million, US$455million) and non-emergency hospital patient transfer (£150million, US$194million).

Setting up the fund was a central recommendation in the UK Campaign for Better Transport’s 2014 Buses in Crisis report, which warned of an impending catastrophe for rural public transport users if new measures were not adopted. One of the most imaginative schemes being funded is being run by the English Midlands county of Northamptonshire, where some 16 million car journeys are made each year, 80% with single occupants.

Its council interprets this as offering 13 million annual opportunities to reduce travel costs and carbon emissions. The pilot has already incubated plans for a joint-venture community interest company (CIC). This ‘social enterprise’ will commission and deliver transport services across 912 square miles (2,364km2), through a consortium bringing together the county government, three local hospital groups and two local universities.

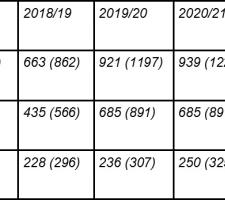

The county foresees considerable financial benefits in efficiency gains through combining contracts and services, with a synergistic approach to data management and analysis drawing on providers’ pooled resources and university research capabilities. Projected results over a five-year period appear in table 1.

The CIC’s first task is collating and analysing currently disparate journey data. As it later decides that emerging technological and service innovations look promising, it plans to offer them to individual agencies and operators to help improve their service delivery.

Nearby Cambridgeshire County Council won one of the highest awards, £460,000 (US$590,000), and has initiated a two-phase exercise focussing on its rural north-east. The first phase began in September 2016 and involves maximising existing resources by taking the calculated risk of allowing the theoretical overbooking of home-to-school buses by up to 5%, to save on unnecessary taxi use, and monitoring the results by introducing smartcards.

This is against a background that on some runs, school buses that were supposed to be full proved to be only 90% loaded. The scheme, due to be rolled out county-wide from autumn 2017, expects to save £900,000 (US$1.17 million) a year on a £9 million (US$11.7 million) bill for school transport. The county is currently considering the feasibility of raising the ‘overload’ to 110%.

The second phase, which started in April 2017, follows on from surveys examining the impact of service cuts on major potential user groups that will be necessary if cost savings cannot be identified through efficiencies and the integration of services. One strand aims to integrate off-peak buses with dial-a-ride requests and community transport visits to senior citizens’ day centres, using specially acquired scheduling and routing software.

With an eye to the benefits of disseminating good practice, successful bidders are being encouraged to share their experiences; and, at project end, deliver detailed reports. Depending on these, the UK government could envisage a wider rollout, with a ‘one-stop shop’ for potential passengers as a key enabler.

As in other European countries, such services tend to be commissioned by staff without transport expertise and delivered by providers with little incentive to seek improvements and savings and are therefore often over-specified in relation to real patient needs.

The thinking is that a Total Transport approach coordinated by local governments experienced in their own social transport operations, could produce substantial savings.

Urban too?

A 2014 Passenger Transport in Isolated Communities report published by the UK House of Commons (lower house of parliament) Transport Select Committee commented that policy makers sometimes equate ‘isolated communities’ with rurality. It found, however, that isolated communities “also exist in urban and suburban areas”.

It went on to recommend that the DfT draft a wider definition for use in targeting resources.

The starting point could be an inclusive ‘available-accessible-affordable-acceptable’ model (see box) which Urban Transport Group director Jonathan Bray told

In response, the department is to look at the feasibility of agreeing a ‘robust’ definition of isolated rural and urban communities and examine the suitability of the model. It has yet to publish its conclusions.

The four As definition

The inclusive transport model states that a community risks isolation from opportunity if its passenger transport network does not deliver:

Availability. It should be within easy reach of where people live and take them to and from places they want to go to at times and frequencies that correspond to their patterns of social and working life. People also need to be kept informed of services that are available.

Accessibility. Vehicles, stops and interchanges (and walking routes to, from and between these) must be designed in such a way that, as far as possible, anyone can use them without difficulty.

Affordability. People should not be ‘priced out’ of using passenger transport because of high fares and should be able to find the right ticket easily.

Acceptability. People should feel that passenger transport is comfortable, safe and convenient and equipped to meet their needs.