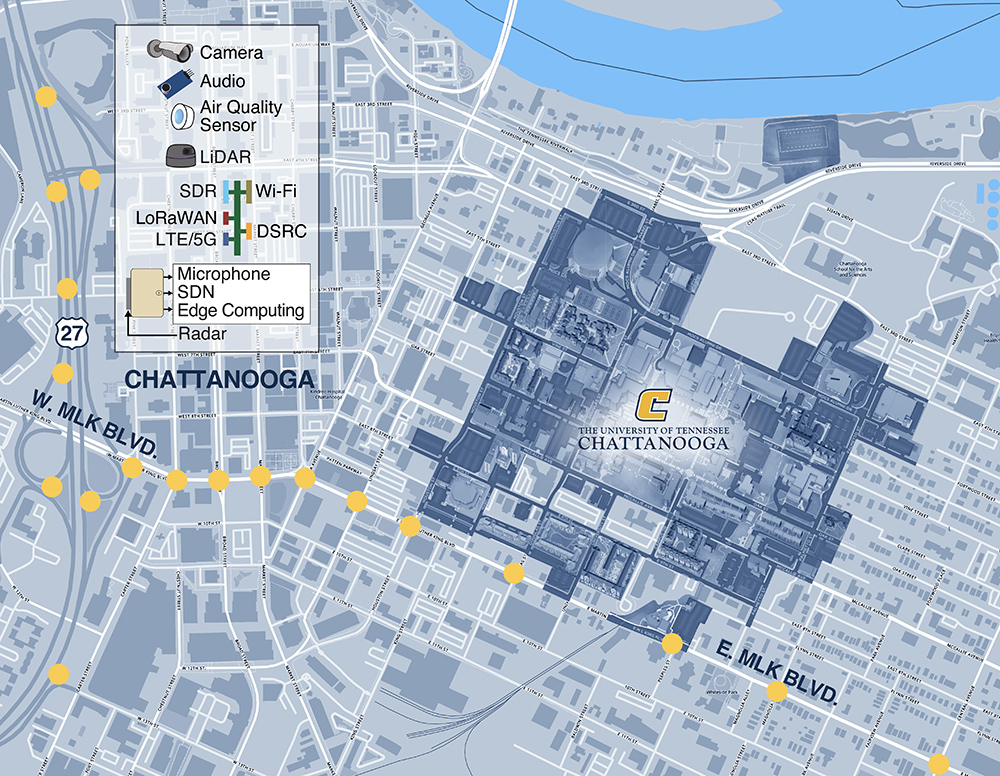

The City of Chattanooga in Tennessee is to build what it believes is the largest smart intersection network in the US, with more than 100 intersections covering the entire downtown area. The US Department of Transportation is giving $4.5 million to the programme – matched by private investors for a total of around $9m - to install a 'living laboratory' throughout 2023 and 2024.

Seoul Robotics is a key player, expanding an existing partnership with the Chattanooga Department of Innovation Delivery and Performance, and the Center of Urban Informatics and Progress (CUIP) at the city's University of Tennessee. Their MLK Smart Corridor testbed, first deployed in 2019, uses Lidar sensors equipped with Seoul Robotics’ 3D perception software SENSR to anonymously detect, track and predict the movement of pedestrians and vehicles.

This delivered “an entirely new dimension of insights beyond what we anticipated," said Dr. Mina Sartipi, CUIP founding director. "The level of accuracy and actionability has enabled numerous advancements in how we can make our city safer, more efficient and healthier for the people who live here."

Step up

That’s not bad from just 11 signalised intersections – although they offered the city one billion data points a day. Clearly 100-plus intersections – the biggest urban Internet of Things (IoT) deployment of its kind in the US – is a huge step up from that, with full connectivity, and a range of sensors as well as edge computing, and a dazzling array of data points.

“It expands the type of research that can be done at this scale,” CUIP Testbed manager Austin Harris says. “The testbed is an enabler for CUIP: for our students, it gives hands-on experience with real-world data and the environment for real-world testing and validation. But at the same time, we see this as a tool that we want to share with industry and other academics, as well as government: you know, if you don't have something we have, come use the environment, let’s update it. So we really look at it as a platform that enables a wide range of research on IoT, ITS, connected and automated vehicles, wireless communications, and so forth.”

“What's really great about the CUIP team is that their goal was to help share this information, not hold it all to themselves and say, ‘Well, look, I succeeded!’” says William Muller, VP of business development at Seoul Robotics. “They actually, truly want to take what they’re learning and help pass it on to other cities. And that's our goal too: they might not always choose us as their vendor - that's fine, but at least we’re allowing them to avoid a lot of mistakes.”

And there should be a rich store of information to share, as Chattanooga intends to use 3D data from the new intersections to prepare for the transition to electric vehicles, mapping the ideal locations to install EV charging stations, and how to best use the ones the city already has. It will also utilise the system's real-time traffic insights to optimise routes in a bid to alleviate congestion and reduce vehicle emissions. The data will also help understand pedestrian movement at intersections and through city corridors, on the road to Vision Zero.

‘Open sandbox’

However, it's one thing having this next-generation testbed, an ‘open sandbox’: but will the citizens of Chattanooga – the drivers, pedestrians and cyclists – actually feel the benefit? CUIP’s goals are aligned with those of the city, insists Harris: for the initial corridor testbed, community engagement was key. “We worked extremely closely with the city,” he says. “The first project we were able to do with Seoul Robotics was around pedestrian safety. The city came to us and said: ‘We want to look at near-miss events, to understand how pedestrians are utilising the intersections and how can we identify high-risk scenarios?’”

With the new, much wider-scale, deployment, the technology will be applied to make a positive impact on congestion, safety and connectivity, Harris says. Seoul Robotics will provide “high-resolution data” from Lidar across the myriad intersections.

It sounds as though Seoul Robotics is in for some long days and nights to get all this kit up and running, but Muller is not daunted by the task ahead. “What we try to do is empower cities or whichever contractor they work with to allow them to deploy and scale the stuff,” he says. “The design has now been built around scaling, so instead of us spending a day per intersection, once installation - which is normally the longest piece – is complete, we try to get the intersection up and running in under an hour. And I believe we're getting to that point. This all goes hand-in-hand with us having a new version of the software, which is built around scaling now, and going into those 100-plus locations easily and rapidly. Because anybody that's hung a camera at an intersection and done the wiring, they can easily do it.”

The really complex bit was always the configurations and set-ups and getting the software and the technologies working, he explains: “That's what we really took care of.”

Deployments at scale

But since the beginning of 2022, Seoul Robotics has been working on making deployments scale as easily, as efficiently, as possible: “We are, if not the only one, then at least one of the very few that gets that part of it, and the importance of that - and has actually achieved that. You see a lot of cool demos out there and fancy videos being played.” But when it comes to scale, Muller insists: “I don't think many of them are in that position as of now.”

Similar testbeds tend to be proof-of-concept affairs, Muller says: “This is the first one that's actually scaling.” And he is excited by the prospect: “We still don't have full visibility. There's a lot of things we’ve still got to learn because now we're going from just a singular intersection point of view to the whole corridor.”

Updates will be made as the project goes along. “We had dedicated short-range radio deployed in 2019,” Harris laughs. “And very soon after that we realised that was the incorrect direction - I'll leave it at that - but we didn't have Lidar deployed in that initial technology stack or design of each intersection on day one. After the first project with Seoul Robotics we learned a lot: we saw extreme value in the data they provided and the system that we have deployed out there, way beyond pedestrian safety, from cooperative perception through the infrastructure.”

Pedestrian insights plus ‘the big picture’ will be what Chattanooga gets out of this, suggests Muller. “I think it's going to be pretty positive. If you think about your base technologies, the things that you utilise to get from point A to point B – maybe a Waze or a Google Maps - you can start planning your journey, you can know where to stop for gas, where you want to go visit something,” he says. “So it's that concept, but at a more city operational level: seeing the big picture from this whole corridor. Where are the choke points? Where are the busy points? How do we encourage people to put their offices there because we know what the foot-flow looks like? Where do we want to add more parks and more restaurants because people gather here or do this there? We’re hoping to see those kind of insights.”