Alan Dron looks at why congestion charging and other similar schemes are so controversial in North America.

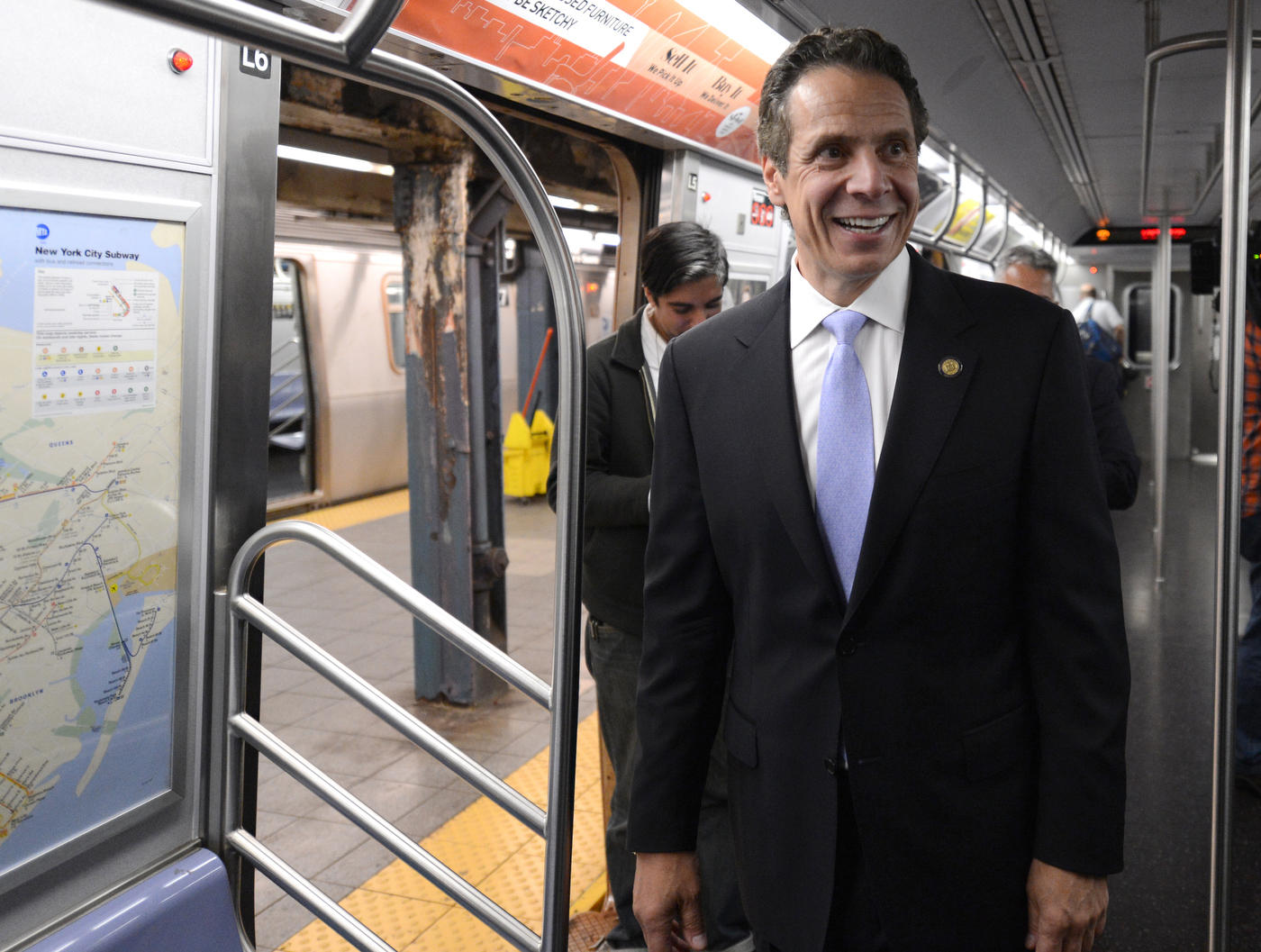

In August, Andrew Cuomo, governor of New York State, described congestion charging for the city as “an idea whose time had come,” according to the Bloomberg wire service. In October, he announced a ‘Fix NYC’ advisory panel to study methods of easing congestion on the city’s streets. Although Cuomo did not specifically mention congestion charging when setting up the panel, he said it would study options for improving traffic flow in the city and report back with proposals in December.

Some city planners in the US have previously toyed with congestion charging schemes, to ease traffic and/or reduce pollution. But unlike cities in other parts of the world, such as Singapore, Stockholm and London, such plans have never come to fruition. Now, the latest attempt to introduce it in New York City again seems doomed to run into the sand unless events take an unexpected turn.

New York City’s mayor, Bill de Blasio, said he “does not believe” in congestion charging and was reported as saying he had never seen an example of congestion charging that he regarded as fair.

And, according to the Bloomberg report, in October he described congestion charging as a “regressive tax. Rich people will pay it without even knowing and poor people and working-class people will really take a hit. And it doesn’t make any accommodation for people who need to go to the hospital, including folks of limited means.”

He had previously stated that the prospect of congestion charging reaching the statute book was “inconceivable” given the Republican-controlled New York State Senate.

Arguably the best chance to introduce congestion charging in New York City came in 2008 under Mayor Mike Bloomberg, who proposed an $8 fee to enter the most congested areas of Manhattan during peak hours.

At that time, according to the New York Times, the city’s transport commissioner, Janette Sadik-Khan, told state politicians: “You are either for this historic change in New York or you’re against it. And if you’re against it, you’re going to have a lot of explaining to do.” This did not play well with state politicians, according to the Times, who regarded both Sadik-Khan and Bloomberg’s attitude as condescending.

On that occasion, it was opposition at both the city and state level that put the kybosh on the scheme. Many New Yorkers regarded it as a tax on moving around their own city, while residents of the city’s outer boroughs saw it as mainly benefitting wealthy Manhattanites.

David Fields, a member of the American Institute of Certified Planners and a principal with transport planning consultants Nelson/Nygaard, believes it will always be difficult to persuade the US public to adopt such a charge. And if it’s unpopular with the public, the politicians who represent them won’t want to touch the idea with the proverbial bargepole.

The major problem, says Fields, is that: “You’re asking people to pay for something that in their minds, historically, has always been free. That’s always going to be a tough sell.

“In New York City specifically, what stopped it previously was that they needed approval from someone beyond the city. They needed state approval and there was no real vested interest to be part of something that was perceived as taking away something that was free. There were no benefits for people who would have to make the decision and defend it.”

There has, says Fields, been a proposal floating around for some time, the ‘Move New York Plan’, which suggests what he describes as a very rational approach of putting tolls on some of the most heavily-used routes into the city, while removing existing charges on bridges that link the city’s outer boroughs that still have spare capacity.

“What people think of as the city is Manhattan. Bridges connect individual boroughs. It would mean taking away charges on certain bridges that don’t come into the main part of Manhattan, in what people call the outer boroughs. This would have the benefit of not appearing as simply taking money from motorists.”

Spokespeople for both New York City and New York State failed to respond to requests from ITS International for further information on the latest proposed scheme.

Americans have long been held to have a love affair with cars, so is the reluctance to introduce congestion charging in North America partly down to culture? “I think so,” says Fields. “I’ll go out on a limb: I think a lot of it comes from the number of people using transit [systems] today. In Europe and Asia, transit use is much higher, so there’s much more incentive to shift dollars into transit systems.”

However, the reluctance to pay congestion charges does not equate to blanket hostility in North America to all forms of road charging: “There are new road projects that are built to be tolled and they’re doing fine.” So, people are prepared to pay for road access, he suggests, but it is the aspect of taking away that ability to make their own decision on whether to pay that rankles.

Will US politicians ever be prepared to back congestion charging? It is “a very new idea for a lot of people and the political realm is where people would go to stop something they’re unfamiliar with. But I don’t think it’s insurmountable.”

The more that people realise, particularly in the most congested areas, that cities can’t solve the problem by building more roads, the more they will realise that there has to be a different approach, he suggests. “I do think it will come sooner or later.”

Fields’ comments are backed up by Prof. Gopinath Menon, senior research fellow at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University. Some forms of payment that are effectively congestion charging do exist in the US in the form of high-occupancy toll (HOT) lanes, “so it’s not impossible” to introduce road charges in principle. “However, those are new highways, so people are prepared to accept it.”

Like Fields, Menon believes that many of the objections to congestion charging stem from road users’ perceptions that they are being told to pay for something that they previously received for no cost. “I think [US motorists] are so used to having a free ride they probably don’t like the idea,” says Menon, who was previously the chief transportation engineer of Singapore’s Land Transport Authority.

The nearest thing to congestion charging in North America comes in the form of toll roads, he notes. Ontario’s Highway 407 Express Toll Route, for example, has cameras located at all on and off ramps, which register a vehicle’s number plate, automatically calculate the toll to be paid and send an invoice to the vehicle’s registered owner. Toll roads or managed lanes are also present in 24 US states, with vehicle-mounted RF tags being used to electronically calculate toll payments.

Singapore was one of the first cities worldwide to introduce tolling for vehicles entering a central business district: “People always say Singapore is special and that it can do things not possible elsewhere,” says Menon. “But after London [introduced its congestion pricing] I think anyone can do it. I don’t see why not. And I think New York is a very good candidate.”

London, of course, saw traffic dip noticeably after the 2003 introduction of the congestion charge for a large swathe of the inner city. However, despite the charge climbing steadily higher, from an initial £5 to £11.50 today, in recent years traffic congestion has climbed back to pre-charge levels. This has been put down to several factors, including an explosion in the number of light vans delivering goods ordered on the internet and the advent of ride-hiring services such as Uber.

Currently, people who use transit systems – who are often the poorer members of society – pay directly for their transport, every time they use a bus, train or light rail system. Car drivers do not face the same direct payment (excluding those who pay the London congestion fee) although they pay indirectly to some extent through taxes and for petrol.

Will New York – or any other US city – ever introduce congestion charging? At present, the omens remain poor.