Gothenburg, January 2013, will be the time and place for the launch of the next city congestion charging scheme in Europe. In a separate development, Los Angeles County’s tolled Metro ExpressLanes began operating in November 2012 – the latest in a series of innovative tolling projects to get started in the US.

While substantially different in shape and form, initiatives in Europe and an expanding number of US States are combining to form a picture – one of road tolling growing in stature as a means for solving acute problems of transportation.

It seems this is partly a sign of the times. Improvements in highway capacity and public transport are not possible for government authorities without funds to pay for them. Tolling revenues are the answer for some, raising revenue needed for improving public transport or expanding road capacity. Then there is the ‘demand management’ role of road user charging.

Public acceptance

Among a section of industry and for a number of years, this has represented a zenith of transportation policy if applied to the full – with variable road use pricing being used to influence if not control travel choices, while raising funds to develop alternatives to car use. Historically, this pinnacle has been hard to reach. Political opposition has been too great, although stances have softened it seems, in the US at least, where the notion of paying a toll for use of additional infrastructure has gradually come to be accepted.“For years road tolling was just about raising money, but authorities have realised that they can apply the technology as a means for meeting policy.

The technology has historically been difficult to implement, but on the whole, highway and transportation agencies now just cannot expand capacity by building new roads.

It’s not good environmentally, there’s usually not room and there isn’t the funds,” says Ken Philmus, a former director of the New York & New Jersey Port Authority and now senior vice president of

Metro ExpressLanes in Los Angeles County is the latest in a list of 11 ‘managed lanes’ projects operating in the US. Not all are the same in detail, but in general each follows the principle of cordoning off existing or new lanes reserved for drivers willing to pay to use them.

How much each motorist pays usually depends on how many people are travelling in the vehicle – solo drivers pay the most. In some cases – as in LA County – charges also rise with demand, measured by falling traffic speed, or with time of day.

The aim is to maintain traffic flow, which is assisted further by the ‘free-flow’ systems being fully electronic with no barriers to impede vehicles’ progress. Furthermore, in most cases the managed lanes are also reserved for buses. “Folk that ride transit get the benefits without additional charge, so encouraging intermodality,” says Philmus.

Means to an end

“When looking at how to get around transportation problems, US agencies are not stovepiping, they are not considering one form of transportation on its own, they are trying to integrate different solutions. But this is not an end in itself – it is a means to an end. The aim is to have good transportation for the economy and for individuals’ quality of life.It is not just about travel times. With demand management pricing comes a way of adding capacity at a lower price than building from new and maximising use of that capacity to get as much throughput as possible. Cities and agencies are beginning to realise this.”

The US express lanes are being proven to work (traffic speeds have reportedly increased by 15-20mph in Minneapolis), according to Philmus, which is reflected in a surge of new project sites being studied for similar treatment Philmus also acknowledges, however, that road pricing – fixed or variable – is not the answer everywhere.

Neither is the European trend for cordon-based city congestion charging favourable in the US. Such a scheme was rejected by New York. “It wouldnt work somewhere like LA where there are numerous centres”, Philmus says.

Hopes holistic

Road charging developments in Europe are being watched keenly by governments elsewhere though, saysIn similar fashion to the Swedish capital Stockholm before it, Sweden’s second largest city has instigated road charging as part of a “whole transportation system”, says Furan. The congestion charge is intended to reduce traffic pollution in Gothenburg’s central district, while raising revenue to fund public transportation, cycling facilities and other ‘green’ initiatives in the city.

“The main motive here is changing demand from car to transit,” Furan says.

“A modal shift of around 10% may be desirable in cities and 25% in rural areas, which raises the question of how much should the cost of rail fares be subsidised? Systems of tolling can allow politicians to do so. It provides funds for infrastructure etc and roads become more tolerable.

In Stockholm, the congestion charge launched in 2006 cut rush hour traffic by 30% and travel times by half.”

Other examples of tolling or congestion charging embedded in a whole system include Oslo, Bergen and Trondheim in Norway.

Trondheim in particular, says Furan, gives a good example of how road pricing revenues can help governments raise much needed funds.

Since 2008, about 60% of Trondheim’s transport funding has come from tolling roads approaching or surrounding the city. “About 40% of revenues have been invested in better roads, around 40% has gone to public transport and 20% to environmental improvements,” Furan says.

Discernible shift

Norway’s city based tolling projects were initiated with a focus on raising funds for transport improvements. “Plus there is definitely now more of a discernible European programme to encourage modal shift, to demotivate car use. It is difficult to build more road capacity in the space available and there is motivation of reducing emissions and improving public health,” says Furan.Evidence of the strength of congestion charging as a means for meeting such aims comes from the study of travel behaviour in Stockholm.

The city’s population has continued to rise since introduction of its congestion charge, but as traffic levels have fallen the result has not been a commensurate rise in use of public transport. “Overall demand for transport services, the number of trips or journeys, has fallen,” Furan says. “The conclusion drawn is that the €1-2 congestion fee, while relatively small compared to London’s £8 charge, is enough to make people more aware of whether they really need to travel or not. And if they do need to make that journey, the charge plants the thought of whether it’s better to take the train instead of driving. A small change in transport cost has produced a dramatic effect.”

Steinar Furan spoke to ITS International from his company’s South East Asia office in the Indonesian capital, Jakarta, where Q-Free is helping city authorities to develop an electronic vehicle enforcement system. Once in force, this will require drivers to fit transponders to their vehicles holding correct registration, tax and insurance details, which will be checked automatically by roadside equipment and by police at arbitrary checkpoints.

A number of cities are investigating such ways of overcoming acute problems of vehicle tax and insurance fraud, Furan says. A highly reliable electronic system is needed to make such an initiative effective at catching offenders. “From there it is a short jump to installing access control, such as restrictions on high emission vehicles,” says Furan. “It is much easier to implement a means for reducing congestion or pollution if an electronic vehicle registration system is already in place.”

Thales’ take on trends in European tolling:

There are three main directions of development in European road tolling, writes

‘Thirdly, regarding urban toll projects, the objective is mainly to fight against pollution and congestion. Paris has introduced a pollution prevention plan that would include the establishment of a toll throughout central Paris, a city which does not comply with current European standards of air quality.

Thales is currently engaged with authorities in preliminary stages of a number of projects, providing technical, financial and operational expertise. Thales supports procedures of “technical dialogue” or “competitive dialogue” in project development, because the great complexity and strategic importance of these major schemes fully justify such exchanges. These dialogue procedures allow industrial companies and operators with real expertise to provide authorities and their consultants with the know-how necessary to ensure the requirements and specifications of the project are perfectly adapted to solving the city’s or country’s particular transportation problems.’

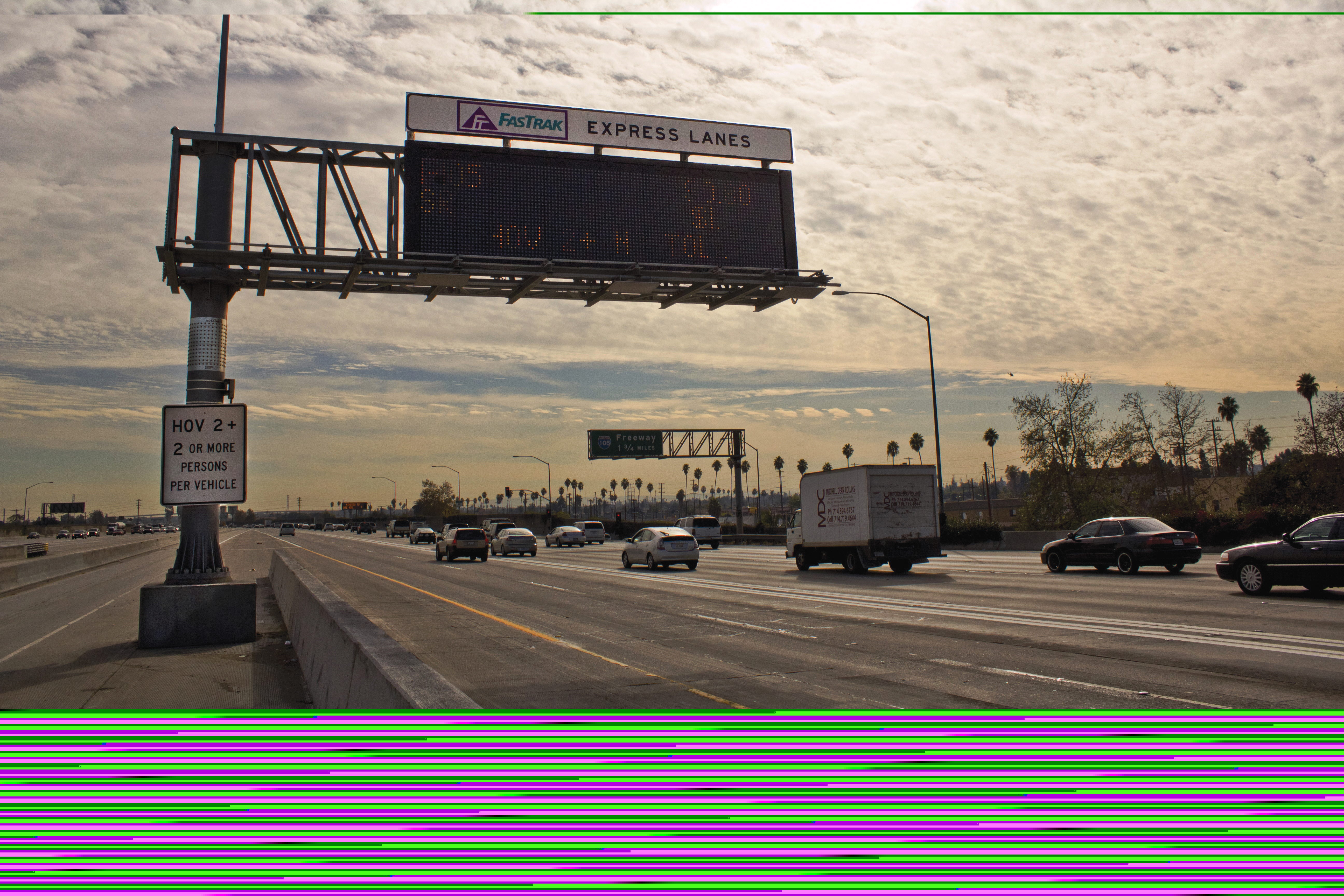

Traffic flowing smoothly on the I-110

Los Angeles County Metro’s ExpressLanes demonstration project was launched on the I-110 Harbor Freeway on 10 November 2012. Shortly after the ExpressLanes were opened, Metro reported traffic was ‘flowing smoothly and the commuting public appeared to be making the transition to the project’s many travel options’.

Solo drivers can now travel in 11 miles of carpool lanes on the I-110 freeway by paying a toll electronically. The project also seeks to reduce the number of cars on the freeway by expanding and improving bus services and other transit options. Metro plans to open a further 14 miles of ExpressLanes early next year, on another heavily congested Los Angeles freeway, the I-10 San Bernardino Freeway.

The ExpressLanes feature an electronic tolling system to automatically assess tolls. All drivers that use them must have a FasTrak transponder that communicates with the tolling system. Metro had exceeded its goal of 25,000 transponders being issued before the I-110 ExpressLanes opening and public demand for the devices remains strong.

Buses, motorcycles and cars or vans with one or more passengers continue to travel toll-free in the ExpressLanes – drivers indicating the number of occupants in the vehicle by moving a switch on their transponders. Solo drivers receive a monthly bill for their tolls.

To avoid traffic queues, roadside sensors have been deployed to measure congestion in the ExpressLanes and increase the toll from 25 cents a mile to a maximum of $1.40 a mile as more vehicles enter the lanes. Overhead electronic signs display the current toll so solo drivers can decide if they want to pay the toll or continue driving in the general purpose lanes.

According to Metro, its ExpressLanes project is the first of its kind in the US to offer an Equity Program that reduces toll prices for low-income families and the first to link transit use to toll credits. Metro ExpressLanes is overseen by Metro, the California Department of Transportation and several other mobility partners. The project has been funded primarily by a $210 million congestion reduction demonstration grant from the