Industry experts talk to Jason Barnes about the legislative situation of current and future in-vehicle systems.

Articles about technology development can have a tendency to reference Moore’s Law with almost indecent regularity and haste but the fact remains that despite predictions of slow-down or plateauing, the pace remains unrelenting. That juxtaposes with a common tendency within the ITS industry: to concentrate on the technology and assume that much else – legislation, business cases and so on – will materialise, somehow, from somewhere.Vehicles’ increasing autonomy is a case in point. We have reached a stage, technologically at least, where vehicles can pilot themselves on our roads with a great degree of independence. High-speed platooning with hands-off driving is nothing new to the ITS industry, the technology having been demonstrated in test conditions by several organisations around the world numerous times now – and often quite some years ago. In the US, DARPA’s Grand Challenge demonstrated, again some years ago, the ability of vehicles to navigate for themselves, first in a desert environment and then later in an urban setting.

Some of the autonomous vehicle research has addressed a somewhat harsher requirement. For instance, taking note of insurgents’ tactics in Iraq, in particular attacks on rear-echelon troops delivering supplies to combat units, the US military has, in an attempt to reduce casualties, undertaken research into logistics vehicles which are capable of operating without humans. Less dramatic applications exist or are emerging. Anti-lock Brake System (ABS) and Electronic Stability Program (ESP) systems are well established, whilst parking and lane change assist are gaining traction in the market. However, as in so many other ITS application areas, technology creep is often unmatched by legislative change. But how do all of these solutions fit into our existing legal frameworks?

To say that nothing has been done is unfair. To give but one example, one of the deliverables of the

The Vienna Convention

The Vienna Convention is seen by many as a sticking point. This international treaty was designed to facilitate international road traffic and to increase road safety by establishing standard traffic rules among the contracting parties. The convention was agreed upon at the United Nations Economic and Social Council’s Conference on Road Traffic which took place in the Austrian capital in 1968. It came into force on 21 May 1977 and has been ratified by 70 countries. Specifically, in relation to vehicle autonomy, Articles 8 and 13 of the Convention state that a vehicle needs a driver and that the driver shall always retain control. Over 40 years have passed since agreement, and 35 since implementation. In that time, the fanciful and unforeseen have been made real. So is it time for a re-think? Does the Vienna Convention need a revamp, or does it even remain at all valid?“A proper look”

What no-one has done, says Scott McCormick, President of the Connected Vehicle Trade Association, is step back and take a proper look at what we should regulate.“Manufacturers are getting round the issue at present by saying that there’s an on/off switch but really they’re just putting the whole issue in the ‘too difficult’ box.

“The Vienna Convention is typical of any homogenised geo-political legal exercise and a large part of it is more concerned with security than safety – fonts and type and where they should be positioned on the vehicle – but is it relevant that RFID or DSRC into and out of the vehicle should be treated in the same manner as a license plate?”

The urgency of a solution has diminished somewhat with economic downturn and the fact that people are now keeping their vehicles for longer, he says. Less than 10 per cent of vehicles in the US are being replaced each year, with average ownership creeping towards a decade rather than the five years of even quite recent times. Market penetration of Connected Vehicle-type technologies is affected, therefore, with any attempts to regulate specific types of technology increasingly meaningless, he feels.

Function, not form

“The key is not to specify the technology but rather the function,” McCormick feels, “to have a situation where you state ‘this is the behaviour/data exchange/manner of participation we want you to conform to’ and then leave industry to marshal its resources and come up with solutions.

Lots of companies have vested interests in particular solutions and we need to move away from ‘what’ to ‘how’.”

In the US, a big issue is the lengthy process involved in instituting new legislation. The

But with the 2016 election likely to delay things further, along with the need for two or more years for implementation, that pushes things out to 2018 at the earliest and possibly 2021.

McCormick advocates taking a more aggressive schedule, noting that cooperative systems don’t start to provide useful information until a significant proportion of the vehicle fleet is participating. Best estimates put the figure at about 60 per cent, which translates to a 2024 timeframe.

And yet, he notes, a rule-making can happen very quickly indeed when there’s the will: “We got a rule-making last year from the federal government which made it illegal to text while driving in interstate commercial vehicles. That happened in weeks, not years.

“Interstate commercial vehicles are the only vehicles that the federal government can mandate regulations for. It can say, ‘all trucks, not just new, must have this technology within two years’. There’s a lot of space inside the cab where this equipment can go and I’d like to see that happen. It would force the certification process along and give the federal government a real-world test. It would sort out the app portals, of which there are almost 80 in the world, and encourage people to think about adding apps such as trailer integrity video.

“None of that requires years of law-making nor privacy issues to be addressed.”

Getting past privacy

Privacy concerns are overstated, he says.“We need to ask ourselves this: are we giving up any more than we already do using our cell phones by using in-vehicle systems? We need an overarching principle and an underlying mechanism to make these things work. That’s what we should be working on – that, and a simple, well-articulated value proposition which will encourage technology uptake.

“But look at the internet as an example – no-one worried about privacy or data ownership for a long time. You had Google capturing metadata on shopping habits, for example. Such things only became issues when some people started to abuse things but over time, as we discovered problems, we fixed things. There’s a saying: ‘A reason is an excuse you thought about for too long’ and we seem to have this angst-ridden situation where we hear that “we don’t have a standard… and better technology could come along tomorrow”… well, that’s life. But get on and make something happen, then you can go and legislate it.”

An absolute need

“On the regulatory front, certainly something is needed – if only because we’re moving towards large numbers of vehicles equipped with significant amounts of technology we need to assert that the driver is at the end of the chain,” says Eric Sampson, visiting professor at Newcastle University and City University London and ambassador for ITS-UK.“It’s one thing to have lots of technology helping vehicles and infrastructure to work in concert or automated driver support systems; they are usually very effective. But what happens if a child runs out into the road and the driver relies on automated braking which fails to operate? The driver has to take responsibility. A comparison is what happens in aviation: the aircrew are there to take control if something goes wrong with an aircraft.”

A closer look at the Vienna Convention underscores just how much it needs, as Sampson puts it, “a good spring clean”.

“It’s when you read about such anomalies as the need for tail-lights on trailers that you realise that a lot of the Convention is concerned with our taking modern technologies onto old infrastructure – where, for instance, modern vehicles were likely to encounter horse-drawn carts and the like. It’s a similar situation to what we have in some parts of China today, where even in cities you’ll still encounter old cars being driven at night without lights on. The technology out on the roads has changed a thousand-fold since the Vienna Convention was written.

“What’s needed is a pretty open talking shop where people can come along and say what the problems are. If you make the process too formal you’ll kill it, because while you’ll see some national differences you’ll also see vested interests – the Germans will turn up with a brief from the auto industry to ‘leave us alone’, for instance.

“But we need to get these issues on the table. And there needs to be a common-sense risk analysis. We don’t, for example, worry ourselves over the spontaneous initiation of airbags as we trundle along the road because it doesn’t happen.

The triggering technology is seen as sufficiently robust.

The same approach has to be taken to these newer technologies. If you take vehicle platooning as an example, there are very low consequences if something goes wrong because all the vehicles are moving at the same speed.

“The Vienna Convention has parts which are obsolete, and parts which are dated. Ultimately, though, you could just have the leanest of all conventions – a one-line statement which reads ‘The driver must retain ultimate control’.”

Paucity of debate

Beyond the intellectualising and pontificating, Sampson worries that, in terms of real progress towards an updated or even wholly new Convention, too little is being done.“There’s some very serious and very good thinking going on about liability and risk but for the auto industry the issue is akin to debates in some circles over female clergy – if you don’t discuss it, it doesn’t exist and so it won’t happen – but it will still be there. UN ECE Working Party 29 perhaps came closest to doing something meaningful but for the most part we all know that the Vienna Convention is out of date.

A lot of people are pretending that things will be all right but the truth is they won’t be.

There’s a prevailing attitude of ‘We don’t need to do it this week, do we?’ Well, maybe not. But we’ve been saying that now for a couple of hundred weeks or more.

“It would be lovely for someone to sponsor this work. The auto industry would probably be seen as having too much of a vested interest but we need someone who’s involved but not committed – someone who can offer what everyone sees as a neutral forum for real debate.”

Defining the technology

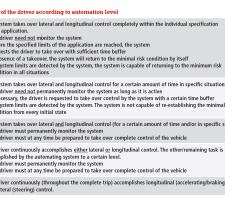

Any debate over the validity of the Vienna Convention has to start with a better definition of what’s actually being discussed technologically, says Tom Gasser of the“Specifically, are we focusing on the higher degrees of automation of the future or todays’ Driver Assistance Systems [DAS]?” he asks, noting that BASt has sketched out five degrees of technological intrusion into the driving task, ranging from totally unassisted driving up to high automation (see Table 1) in order to cover what we have today and out through the near-, mid- and longer-term.

From a legal perspective, Gasser notes, the Convention is regulatory law which obligates signatory states. The Convention makes statements regarding the driver’s duties just as national road traffic codes do – specifically, in Articles 8 and 13.

“That means that the final decision should always be left to the driver and mostly translates into allowing override-ability.

“I don’t think today’s DAS are in conflict with that sentiment, nor are those just about to be introduced; the data supplied by current and near-term sensors aren’t up to the task of taking decisions over and above those taken by the driver. Thus far, then, the Vienna Convention is no ‘roadblock’ to deployment. ABS, ESP and Adaptive Cruise Control [ACC] all remain within the bounds of the Convention. Even emergency braking does; that only intervenes in the last few milliseconds when it could be argued that the driver isn’t reacting.”

ACC systems for longitudinal control and lane-keeping systems for lateral control are already on the market and available in one and the same vehicle, even if they are sold as discrete systems. It is perfectly possible to combine these to semi-automate the driving task, however their actions will still be fully monitored by the driver.

But looking farther into the future there is the potential for conflict. High automation takes the driver out of the equation completely, absolving him or her of responsibility for the driving task and allowing him or her to concentrate on other matters.

With high automation, we move towards the artists’ impressions seen at past ITS World Congresses and in motor show brochures, where for example the driver is effectively in a mobile office and is writing and emailing whilst on the move. We reach a point where if it is the duty of the driver to monitor the driving task, there is a clear regulatory conflict and, effectively, systems cannot be used legally.

“That conflict needs to be recognised and understood, and the interplays between legislation such as the Vienna Convention and national road traffic codes need to be assessed,” Gasser states.

Creeping liability

When it comes to the issue of liability, the auto manufacturers face a substantial risk and a severe challenge in procedural law when, in the case of an accident, the vehicle owner claims that a DAS didn’t work as it should have. That risk increases with the degree of automation.“The situation becomes very interesting once we reach the stage of high automation where a driver can turn fully away from driving,” Gasser continues. “Every accident while engaging the automated mode will then imply a system defect if the driver did not intervene and the damage has not been caused by a third party in sole responsibility. If we look at Day One applications of high automation as are suggested today, such as platooning where vehicles are moving at high speeds just centimetres apart, we can’t expect a driver to react in time. Calling a driver back to the driving task requires a certain time buffer and the precise need and effects aren’t yet fully understood. That needs further research – most of all by psychologists.”

Conclusions

As has often been written in these pages, technology is not an issue. Engineers need policy direction, however, and that in part has to stem from the prevailing legislative situation. A Convention which is now over 40 years on from its inception cannot hope to have kept pace with technology – particularly electronics and ICT.Suggested solutions range from the pragmatic and market-led (McCormick’s advocacy of deploy-and-then-legislate) to the pragmatic and theoretical (Samson’s desire for a less formal talking shop able to avoid becoming bogged down in vested interest).

A common theme is to be sure just exactly which technologies are under discussion, and why; McCormick goes even further and suggests that we ignore the technology entirely and concentrate instead on desired capabilities.

If privacy is in reality a non-issue, then liability continues to hang over the industry like a Sword of Damocles and there needs to be a more concerted – and vigorous – attempt to reach consensus.

What is certain is that the Vienna Convention, fudges and work-rounds notwithstanding, is struggling, and that continuing to put it – or any update/successor – on the ‘too difficult’ pile is no solution. Rather, it is becoming less and less of a solution as more (and more advanced) technologies and applications near market. If we do not address the legislative situation, we face a point in the very near future where it is the biggest single obstacle to deployment.

Addressing the hybrid/EV issue

Another convergence issue which requires a legislative perspective is hybrid/electric vehicles, says McCormick. Although he doesn’t see these as an environmentally valid solution in the near or mid- term, they do need communications and data to address range anxiety and other issues.

“What we really need to do is evolve our transportation needs intelligently. If you’re a utility company with 100,000 vehicles plugged in at peak time, do you want all of those vehicles charging up? No. You want to suck the energy out of them and recharge their cells just before they’re needed. That obliges owners and users to engage and give up information on their intentions and needs – and if they don’t sign up to say, “I go to lunch at so-and-so time and leave work at…” then you charge their vehicles last.

“But when it comes to deployment of the smart grid, almost no department of energy in the world will provide direct guidance. It’s all devolved. People are naively expecting guidance from above when the people you really need it from are the constructors and operators of the grids. That has to be recognised and we need to start doing something about it.”