A UK parliamentary by-election last year – caused by the resignation of former UK prime minister Boris Johnson - highlighted an issue I’ve come to think of as ‘the city island’ problem. Or maybe that should be ‘the city traffic island’ problem.

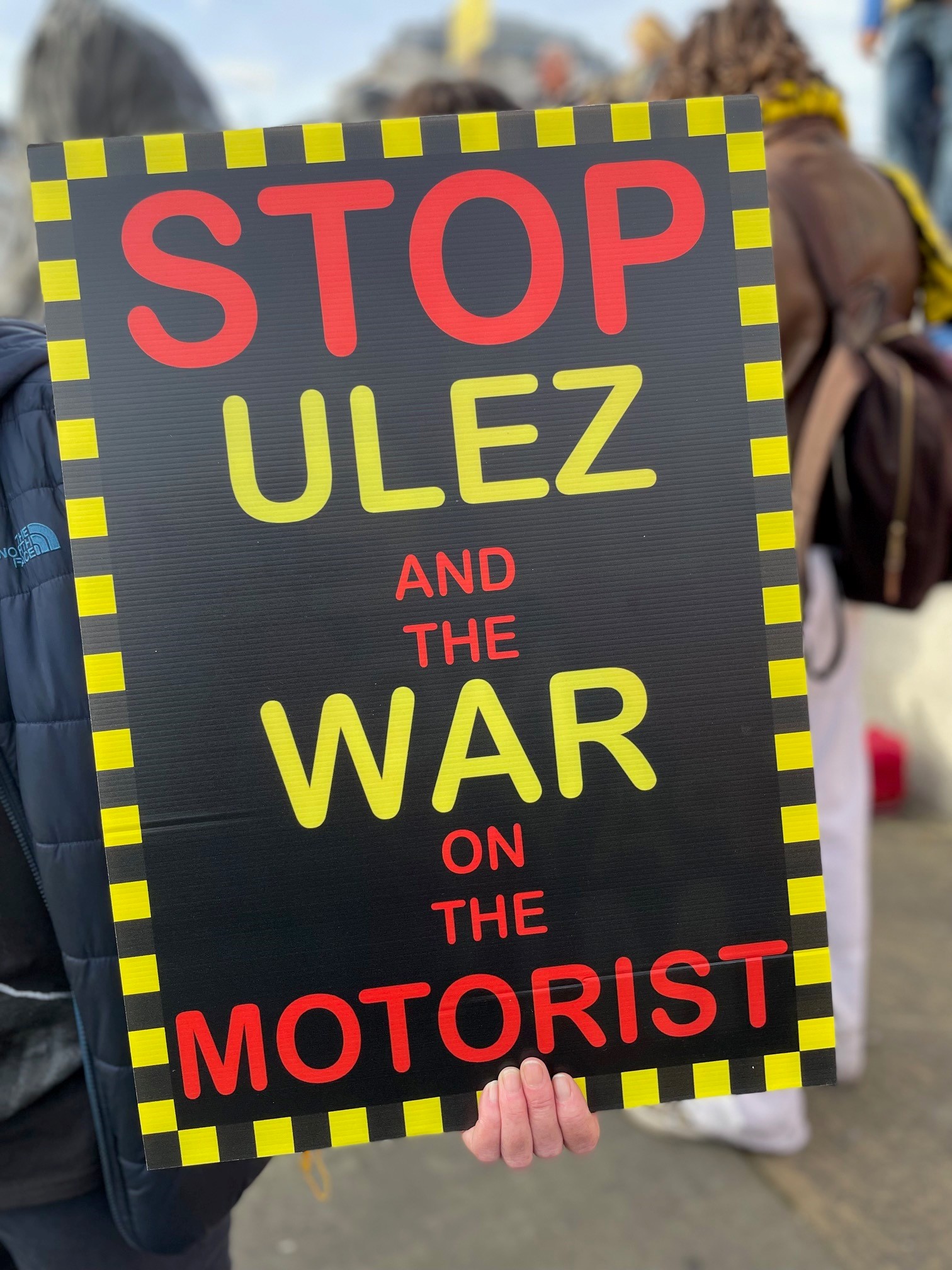

Uxbridge is an area at the western edge of London. The topic that is attributed with a (very marginal but unexpected) win for the incumbent Conservative party in the by-election was that of the ultra-low emission zone (ULEZ).

The ULEZ is a measure to address poor air quality, first introduced in central London in 2019 and expanded to include all areas within the inner city ring road in 2021. Vehicles with high emissions are discouraged from entering central London by a charge. This measure has resulted in a dramatic drop in number of older and more polluting vehicles – both commercial and private – driving in central London.

The ULEZ has been measurably and significantly successful. Since its introduction in 2019, emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) are estimated to have been reduced by 23% and particulate emissions by 19% in the ULEZ area. Air quality in central London has improved substantially, with reductions of 46% in nitrogen dioxide concentrations (and more in some places). The success of the scheme in inner London has been extended by expanding the area to include outer areas such as Uxbridge in 2023.

At this point, however, the good news story has received a setback. Rather than welcoming the development to improve air quality in outer areas, a high-profile campaign against the expansion of the ULEZ became one of the rallying points in the recent by-election.

Unpicking the issues here and working on solutions, I suggest, will be one of the great challenges for transport practitioners, urban planners and all those concerned with air quality and carbon reduction in the near future.

Solving the city (traffic) island problem will need to combine practical and social measures and recognise transport equity – otherwise it will continually pit inner city dwellers against the suburbanites and threaten cleaner air, less congestion and lower emissions across the board. It is not just a London problem, but one that is repeated across European cities, with varying responses.

The trouble with London

London shares characteristics with many cities. It has a central core with excellent connections by public transport, an increasing number of great active travel routes plus multiple other options including cycle and e-scooter hire schemes, car clubs and the like. This central zone is surrounded by a penumbra of less dense areas with lower levels of public transport, poorer active travel infrastructure and fewer choices in the shared transport sector.

Whilst many people see travelling less by car as an ideal, the reality is that this is much more difficult the further they live from the city centre. Indeed, maps of car ownership and usage and transport availability correlate strongly. The further someone lives from the city core, the less dense public transport is, and the less dense public transport is, the more cars people own and the more mileage they travel by car. In outer areas the car has become the default choice and, for many, life is unimaginable without being able to drive in the current conditions.

This motif is not unique to London. It is repeated in cities across the world – although the boundaries, distances and even electoral or administrative zoning may not quite be the same.

It represents a very real challenge to plans to decarbonise transport, to reduce congestion and to improve air quality. Whilst city centre dwellers are often happy with their choices they can be puzzled and even dismayed when their suburban counterparts travel from their outlying homes into the urban core. If no-one in your block owns a car, where does all the traffic come from? Equally, suburbanites see no alternative to their car – and expect to be able to drive anywhere they like.

Berlin: doughnuts and controversy

This pattern was highlighted in Berlin in 2023 when Berliners were divided in an acrimonious election. Berlin is a thriving European metropole with a dense core and diffuse outer area. In the 2023 election the strongest parties emerged offering polar opposite transport policies. The Green Party has consistently proposed policies to reduce reliance on the private motor vehicle as part of efforts to reach net zero – supporting public transport and active travel in particular. The more conservative CDU took the opportunity to make equally strong promises to allow people to keep their cars. The election outcome is distribution of representatives forming an almost perfect doughnut. Inner areas are comprehensively Green and outer areas almost exclusively CDU.

The resulting administration immediately began to pit the desires of those living largely car free in the urban core with suburban dwellers’ requirements that they should be allowed to drive – and park - wherever they want. Instant controversy was generated when the CDU demanded that a network of already planned new cycle lanes be cancelled if they remove a single parking space. In response, central dwellers – and particularly cyclists - have taken up demonstrating to protect plans for reallocating car lanes to bike lanes.

This is one illustration of the urban/suburban split – and an outcome precipitated by the combination of central and outer zones in one administrative area.

The administrative situation in Paris is slightly different. The mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, first elected in 2014, has presided over wholesale changes in the apportionment of road space, reducing car access to the grand boulevards of central Paris and creating a network of green painted segregated lanes for cycles, e-cargo bikes and e-scooters.

Paris’ Plan Vélo

The Paris equivalent of the ULEZ, Paris Respire, was launched in May 2016. In 2017, the first permanent low-emission zone was introduced, the Zone de Circulation Restreinte (ZCR). Following the success of the ZCR, in 2019 the first metropolitan LEZ was set up, banning diesel cars made before 2006 from the city centre. The current Low Emission Zone permits only vehicles with the lowest emissions into the area from Monday to Friday, between 8am and 8pm.

Hidalgo also launched a comprehensive and well-funded ‘Plan Vélo’ (2015-20) which created cycle ‘expressways’ along the north to south and east-west axes, the banks of the Seine and to access the parks of the Bois de Boulogne and Vincennes. A secondary network of quiet ‘cyclable routes’ creates a network at local level. Importantly it also provided over 10,000 cycle parking spaces. The package also included subsidies for people buying e-bikes and cargobikes. Roads were further calmed with almost universal 30km/hr speed limits and more road space was reallocated to bus and tram routes.

This radical activity was followed up by plans to remove 72% of on-street parking and making all streets cycle-friendly in Mayor Hidalgo’s 2020 campaign for re-election. Since re-election she has announced further bold measures to restrict traffic, including a new Low Traffic Zone, active from 2022, which will prevent non-residents’ cars and vans from crossing the city centre at all, and a high-profile plan to remodel the Champs-Elysées as a pedestrian and cyclist-friendly linear park. In a March 2020 interview with The Guardian, Hidalgo made her position clear: “We’ve given vehicle owners plenty of notice so they cannot complain they were not warned. The place for the car in our city will be reduced even more with more alternative mobility available like bicycles, more buses and car sharing.”

Whilst the impact on central Paris is better air quality and quieter streets for inhabitants, the surrounding area, the other seven departments which make up the Île-de-France region regard the changes much less favourably. In common with outer London, these other areas have significantly poorer public transport.

People drive more – and expect to be able to drive into central Paris. They have no influence over the elections in central Paris, however, so there’s no electoral impact on the Mayor. Indeed, there was vocal opposition to her re-election, however given the result, the protest is more likely to have come from outer areas than her electorate in the centre.

It’s notable that there has been recognition across the Île-de-France zone that the public transport situation requires improvement for people in outlying areas. The transport authority, Île-de-France Mobilités has recently made considerable investments in the greater Paris region, including new express routes to connect outer and inner Paris better and on-demand bus services in outlying areas to ensure that people can connect with rapid transit even from low-density areas.

Free public transit in Luxembourg

Meanwhile, less politically fraught measures in Luxembourg are still at the mercy of the inner/outer split.

Luxembourg is a prosperous city state (residents enjoy the world’s highest per capita income of any independent state worldwide). This prosperity has enabled a very high level of car ownership – and by 2020 the highest car density in the EU (696 per 1000 people vs an EU average 560). High car ownership also came with extreme congestion and high emission levels.

To tackle congestion and emissions, the government made all forms of public transport in Luxembourg free in March 2020. The launch of free transport coincided with the Covid pandemic, making subsequent impacts difficult to disentangle from the impact of the pandemic, which suppressed both passenger numbers and new car registrations.

Some indicators can be seen, for instance in passenger numbers on trams which have risen from 22,000 tram journeys per week in 2018 to 88,000 per week in 2022. Car registrations are difficult to follow because of the impact of the covid pandemic, however they have remained lower than the years preceding 2020. That said, independent research has found only a small impact on traffic levels.

This may be for several reasons. Primarily, there’s a strong car culture in the country and the lowest petrol prices in Western Europe. Changing deeply embedded behaviour and values is no short-term project. In addition, population growth within Luxembourg will swell car as well as public transport numbers.

However, there are also significant external factors. The population of Luxembourg is 630,000, however this number is augmented daily by 230,000 commuters from neighbouring Belgium, France and Germany. This pattern is driven by a thriving economy and jobs market, coupled with the very high cost of housing in Luxembourg. The net result is that there are substantial commuter flows crossing the border. Whilst these commuters can benefit from the free transport within Luxembourg, at the start of their journeys, beyond the country’s boundaries, they are liable to pay fares.

A detailed analysis of the impacts of the free public transport policy found a small positive impact in favour of public transport for people living in Luxembourg, however a much more mixed result for cross-border travellers. Whilst some cross-border travellers benefited and chose public transport this was more pronounced for shorter trips. The researchers also noted that cross-border travellers experienced ‘a significant increase in their travel time if using public transport, and indeed resistance has been observed in the expected modal shift’.

The response is a plan to improve access to Luxembourg free public transport from beyond its borders. This involves increasing the number of seats on commuter services to France by 50%, the frequency of trains and investing in services crossing the border (even on the French side). At the same motor vehicles are attracting a new carbon tax.

A repeated patter in transport planning is an extreme focus on city centres - dealing with dense populations offers a great return on investment. However, until we look at the whole system these schemes may not always yield the desired results because people living outside the core urban areas have a huge impact on city centres.

To misquote the great English poet John Donne, ‘No city is an island entire of itself, every city is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.’

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Beate Kubitz is an independent researcher and consultant. In 2020 she was granted a Foundation for Integrated Transport Fellowship to study traffic flows between urban and rural areas. Her forthcoming book on Mobility as a Service will be published this year