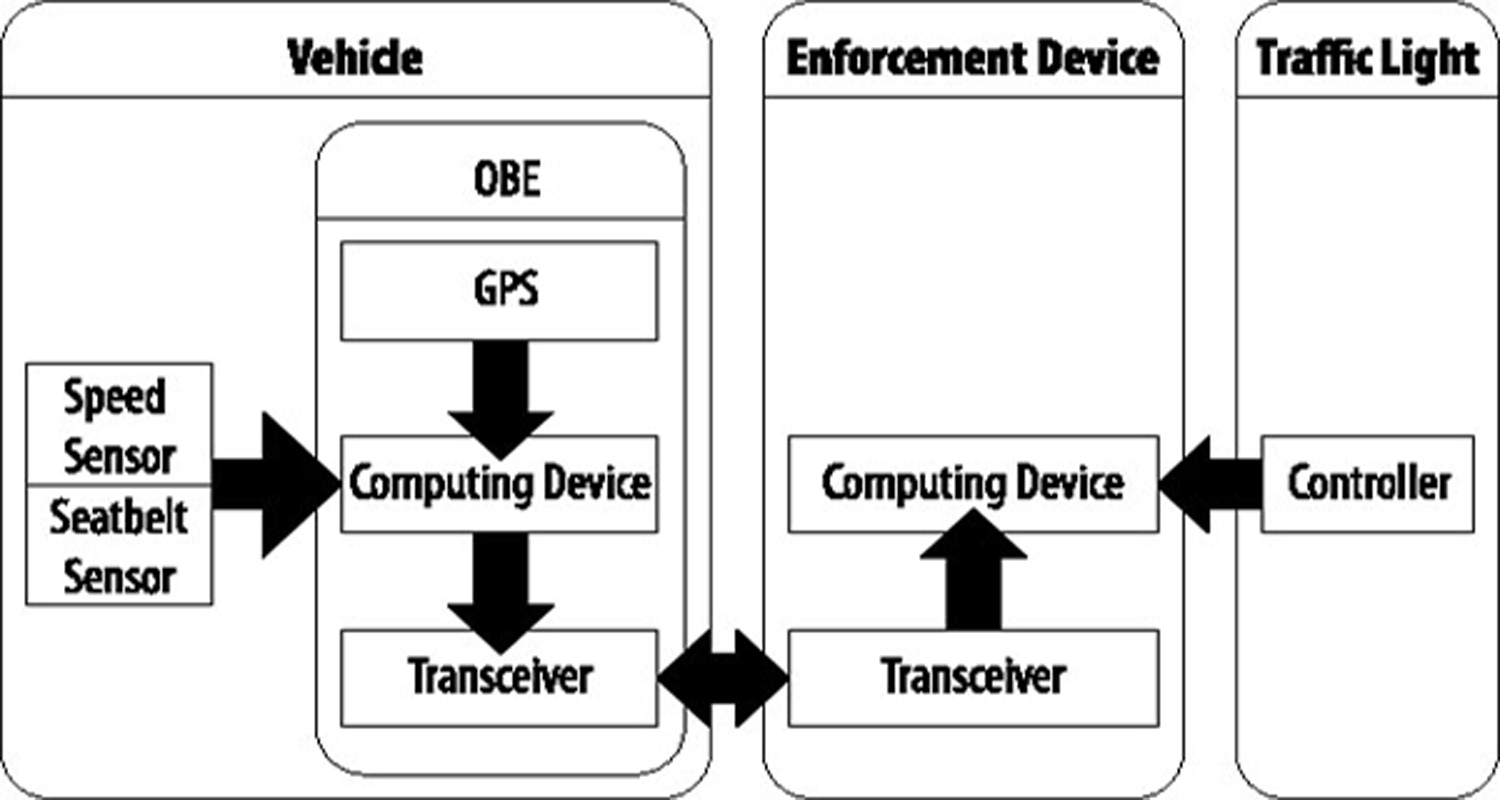

Kim's System block diagram for in-vehicle enforcement

David Crawford explores new initiatives in enforcement

Achieving the EU’s new road safety target of reducing road traffic deaths by 50 per cent by 2020 depends on removing legal and institutional barriers to the deployment of new enforcement technologies, stresses Jan Malenstein. The senior ITS Adviser to Dutch National Police Agency the KLPD, and a European-level spokesperson on road and traffic safety, points to the importance of, among other requirements, an effective EUwide type approval process for freshly emerging equipment.New technical opportunities are emerging on both sides of the Atlantic for applications, including the combined operation of for example speeding and red light running enforcement, and automating safety compliance. One proposal from the US envisages a ‘Holy Grail’ of automatic enforcement from within vehicles; while, in Europe, the role of passive enforcement is gaining increasing emphasis.

To take one area where relatively limited technical intervention could produce disproportionately beneficial results, enforcement of the use of seat belts and other restraint devices (such as children’s seats) currently relies on the use of physical and necessarily random observation by police officers. Yet buckled seat belts can be the single-most effective traffic safety device for preventing death and injury.

The US

But, according to the US National Occupant Protection Use Survey (NOPUS), which provides the only probability observed data on seat belt use in the country, of the 25,351 passenger vehicle occupants killed in fatal crashes in 2008, over 50 per cent were unrestrained.

Since seat belt use (or lack of it) is visible to the human eye, it is also capable of being detected automatically by means of digital imaging technology. The main requirements are sufficient colour

contrast with the seat itself, a shallow camera angle (of about 15° in relation to ground level) and allowance for different windshieldconstructions – with, preferably, an additional light source on the side of the vehicle.

In Europe, a Finnish pilot has demonstrated the potential but further technical innovation is feasible.

Says Malenstein: “It would be possible to introduce an automatic interlock with the ignition system. But, strangely enough, this meets resistance from car manufacturers, who claim that their customers would not accept it, and would rather invest in warning systems. A technology solution for 24/7 enforcement of seat belt wearing would substantially promote compliance and relieve pressure on human resources.”

Drawing comparisons

There is a natural analogy with alcolocks, developed initially in the US in California and, in Europe, in Sweden, where they are now commonplace on commercial and private vehicles (they are also compulsory in public service vehicles in France). One in three of all traffic accident deaths in Europe are alcohol-related.Conventional alcolocks link a breathalyser wirelessly with the ignition system to prevent drivers who are over the drink-driving limit from starting their vehicles.

A recent alternative, awaiting large-scale testing, involves the use of sensors in the steering wheel that measure the proportion of alcohol in sweat on the palms of the driver’s hands.

In 2009, the Dutch Parliament decided to introduce an alcolock programme for serious offenders; and, in 2010,

Experience in Canada and the US has shown that alcolocks can lead to lower conviction rates of between 28 per cent and 65 per cent (the latter threshold being achieved within the first year after installation). Rates of repeat drink driving offences drop by between 40 per cent and 95 per cent.

Holy Grail

US researcher Gilbert Telin Kim, of the University of Massachusetts - Amherst, wants to take the technological approach still further. He has a vision of a coordinated system for the enforcement of safety compliance and other traffic violations – for instance, speeding and red light running – from within the vehicle via DSRC.His concept is of a single onboard unit that would transmit four basic pieces of information (vehicle ID; vehicle speed; vehicle location; and safety compliance status) from a vehicle-mounted transceiver to an enforcement infrastructure or police vehicle using either V2I or V2V communications

The GPS-equipped OBU, with input from speed sensors, would continuously monitor vehicle location. The enforcement system would integrate the resulting output with for example red light status data from traffic signal controllers and advisory speed limits.

Red light running and speeding are closely linked, since the severity of the former reflects drivers accelerating in the hope of getting through the intersection on the green or amber phase.

NHTSA reports red light running as the cause of 92,000 annual crashes on the country’s roads, resulting in some 950 deaths and 90,000 injuries a year – making this the worst safety problem at signalised urban intersections. Occupant injuries occur in 45 per cent of cases, as compared with 30 per cent for other crash types.

Speed enforcement at all stages would be a strong deterrent to speeding up when approaching a signalised intersection, suggesting genuine scope for combined enforcement technology.But there are institutional and organisational barriers.

Traffic signals, for example, operate in their own organisational domain and are not specifically designed as means of enforcement. Combined enforcement would need the installation of additional equipment integrated with the red signal and integrated into a traffic management centre with the agreement of its management.

Malenstein also sees objections to Lim’s idea of an overall invehicle system on the grounds that evidence of dangerous driving depends largely on the evidence of human observations, which a fully electronic system lacks. He cites “a general principle in law enforcement that there cannot be self-inflicted enforcement”.

“It might be possible to couple electronic systems to human observation, as is the case with camera enforcement where the camera ‘eye’ is a substitute for the human eye. But again that could count as being self-inflicted.”

He also raises the question of the cost of DSRC. Kim admits that the feasibility of his concept depends on the mass production (and hence low cost) of the transceiver.

Overall, Malenstein makes an increasingly significant distinction between active and passive enforcement, the former defining the scope of official intervention and penal methods of dissuasion. He sees scope for the greater use of ITS technology in the latter - in the form of spin-offs from the cooperative driving and advanced driver support systems currently being developed and brought to market by the industry for improving road safety.

These can either be integrated in the road infrastructure or installed as intelligent tools giving information and warnings to encourage safety compliance. Here he sees important roles for DSRC.

DSRC – a part to play

“Systems that interact with the vehicle, the driver and the immediate environment have huge potential for application to passive enforcement without the use of any repressive measures.The problem is that this potential is not being sufficiently recognised by the authorities, automotive manufacturers, or even drivers themselves.”

But enforcement agencies, he says, have gained the vision thanks to the EU-funded 2006-8 Police Enforcement Policy and Programmes on European Roads (PEPPER) project, which set out to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of the police enforcement of road traffic infringements, with particular emphasis on speeding, drink driving and the use of seatbelts.

“It can be assumed,” says Malenstein, “that systems such as these will, in future, act as substitutes for active enforcement to what may be a considerable extent. It would be worthwhile to study the area in more detail”.

This trend mirrors the path being taken in the development of Intelligent Speed Adaptation (ISA) systems. Trevor Ellis, Chair of

“However, many satnav systems now have geographic speed limit data, and can be set to warn drivers if they exceed the speed limit. This is close to what the original ISA developers had in mind as an advisory system.”

Malenstein points to research showing that advisory ISA can achieve an 18 per cent reduction in road traffic accident deaths, and evidence from EU pilots that “there is a majority support for advisory ISA technologies. They will reduce the need for traditional police enforcement of speed limits and can replace costly physical measures currently used to obtain compliance.”

Two visions of the future, in other words: one, from the US, of totally automated active enforcement from within the vehicle; the other, from Europe, of increasing reliance on heavily technology supported passive enforcement.