OpenSpace describes itself as a “deep tech start-up building cognitive digital twins to improve the human experience of the built environment”. Roughly translated, this means the company uses vision technology and artificial intelligence to create digital copies of real environments, in order to track how pedestrians are moving through them.

The UK-based start-up’s digital twin platform - deployed at St Pancras railway station in London last September – is a ‘copy’, allowing users to put real-time information onto a 3D virtual replica of the station environment.

It detects and visualises, among other things, the space between passengers in real time, predicting how journeys in different ‘versions’ of the station could be made more efficient.

The Covid-19 pandemic has thrown up some interesting results: OpenSpace detected a 90% drop in passenger numbers at St Pancras after lockdown measures were introduced on 23 March, compared with a weekday in January this year.

And with the introduction of strict new public health measures, OpenSpace has discovered a new use for its passenger movement monitoring tech: tracking social distancing.

The company says this will provide a useful indicator of public adherence to government guidelines, especially in the future when lockdown measures are lifted in stages – and the authorities will also be able to compare historical weekly and daily information for trend analysis.

The project, funded by the UK Department for Transport and Innovate UK, uses Xovis 3D cameras with edge-processing capability and computer vision technology to measure passenger flow rate and travel patterns.

OpenSpace claims the system can pinpoint how the station is performing on various measures, with hard data allowing improvements in real-time crowd management, safety and the overall experience of those who have to negotiate escalators, concourses, stairwells and fellow travellers to get to their platforms on time.

OpenSpace CEO Nicolas Le Glatin believes that accurate crowd modelling improves the understanding of customer experiences – particularly the frustrations which can arise – and therefore allows for better design and operation of these busy public places.

“Our technology is designed to detect real-time passenger separation to alert station managers to current and future overcrowding, and suggest interventions,” he says.

Movement tracking

His expertise is in tracking the movement of people in different environments in order to make those places more efficient and user-friendly. “Pedestrian simulation didn’t exist 10 years ago,” he tells ITS International. Trying to work out how people can best move through a space – not just now, but in five, 10 or 20 years’ time – needs more than guesswork: data is the key.

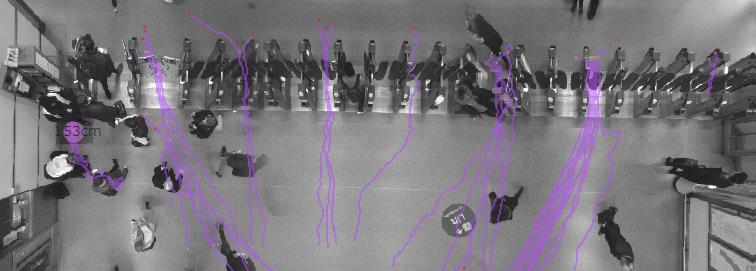

At the heart of the solution is the stereoscopic camera technology which helps OpenSpace to build up the digital twin. The system generates ‘traces’, ghostly purple-coloured lines on a display, which show movement. These source traces go back automatically to OpenSpace’s database on the cloud. “We export the measurements, the real-world data, into the digital twin. So we bring that data captured in the real world into our own digital infrastructure,” explains Le Glatin.

The traces which operators can see are “actually following the people as they move through”.

The same sort of idea is used in the retail sector to monitor the number of people who come into a shop, with resulting in-store analytics used to boost sales. “We are pushing the limits of the technology,” says Le Glatin. “Of course, counting is important for us, but we are also discovering that the use of those purple traces is a wonderful asset to us.”

The OpenSource team could see, for instance, that the purple traces were only going through a few gates in certain places, at certain times, at St Pancras. “Bottlenecks are where the flow is reduced, so that’s really where you want to monitor. That’s where really capacity counts.”

Real-time monitoring of crowd density for the purposes of maintaining social distancing is an interesting – if unexpected – use for the solution, but there are other mobility contexts in which it could be employed. “The same would apply to tube stations, bus stations, anything to do with transit really - anywhere where people are moving, and you might want to establish exactly where they’re going,” says Le Glatin. “Then we can contribute to solving many different types of problems that sit today in different disciplines.”

For example, helping people on city streets to have a more appealing relationship with the built environment generally – including, perhaps, how to be safer at urban intersections and road crossings - although this is not something that would work for entire cities at the moment, he thinks: “We’re not necessarily at that scale yet.”

The St Pancras project is interesting for a couple of reasons. One, it shows the way that technology and good ideas can be adapted according to circumstances. Secondly, while it identifies people movement, it does not identify people themselves – there is no facial recognition element, which may reassure those worried about intrusion into their privacy in public spaces.

Le Glatin studied automotive engineering design in the UK and sees a link with that discipline and “open spaces and data, visual platforms”.

“The concept of digital twin also exists in the automotive industry,” he adds.

Proven technology

The system needs to translate data into a tangible picture of what’s happening. The simulators learn how to make use of source points to automatically recreate movements, automating movement on railway station platforms and concourses. But to do this, the system needs to be fed with data.

“We try WiFi, we tried Bluetooth, we looked at infrared counting,” Le Glatin says. “And we’ve also looked at CCTV footage and I came to the conclusion that none of those technologies have the answer on their own.”

Although not the cheapest option, he was impressed by what Xovis had to offer in terms of proven people-tracking products – particularly at airports and shopping centres - with the ability to measure key performance indicators such as footfall, queue length and waiting times which retailers use to optimise customer experience and increase revenue.

“There has been a significant development in technologies and capabilities in the world of 3D cameras,” he goes on.

Le Glatin is at pains to emphasise again that the cameras do not identify individuals: “We are not in the business of covering the world with cameras.” At St Pancras, the cameras are positioned several metres up, looking down on the tops of passengers’ heads, tracking people within their field of vision to a centimetre-level of accuracy.

“So anything that can help us in that collection of data - as a collection of behaviours - is something that we want to be able to bring to the platforms for applications where our clients have problems that we can fix.”

As the Covid-19 crisis continues, the technology might come into its own even more. “With accurate measurement of people we can learn about social distancing.” He suggests it might be useful to bring, say, an epidemiologist alongside the team “to learn whether there are bottlenecks – the gate line, escalator, lift – which are more prone to transmission”.

The significant amounts of data generated could be used to “better understand whether there are mitigation measures we can learn to minimise transmission.”

These could include markers on the floor to indicate how far apart people should stand when they are in a ticket hall or waiting for a train, for instance. And this in turn has massive implications for transit. “That will have a huge impact on capacity,” Le Glatin points out.

“Transport is about moving people fast and efficiently. So how should this asset be configured to support a return to the norm so we don’t end up with huge queues? That’s what transpired out of our use of the Xovis technology.”

But the vision tech has shown something else that is very important – for governments, transit authorities and individuals – as lockdowns are eased through the Covid-19 pandemic.

The world will, at some point, get back to ‘normal’, and having this sort of data will help. “It’s going to be a fine balance for all of us,” Le Glatin concludes.