Professor Donald Fisher has spent 15 years identifying factors that increase the crash risk of novice and older drivers. His findings highlight the difference between living and dying, Colin Sowman reports.

Motivation for combating the problems associated with novice and inattentive drivers was not difficult for Professor Donald Fisher, the recently retired head of the University of Massachusetts Amherst’s Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering. He only needed to look through his office window to see the scene where a driver knocked down and killed a student in a collision that an experienced and attentive driver would have foreseen and avoided.

“The crash rate in the first six months after drivers get their licence is horrific: nine or 10 times higher in terms of fatalities per vehicle mile travelled compared with middle-aged drivers,” he said. In order to understand this disparity he and his team of researchers have examined two possible causes: that novice drivers may disproportionally allow themselves to be distracted by tasks inside the car; and that they do not recognise hazardous situations as well as their experienced counterparts.

The

“Distraction is part of the reason teen drivers are crashing and I think it is having an effect on older drivers too,” said the professor.

Existing driving simulator work found 20% of glances away from the road are longer than 1.6 seconds and these lead to 80% of the simulated crashes. In naturalistic driving studies, glances away from the road of longer than two seconds have been shown to triple the crash risk.

Just a quick glance?

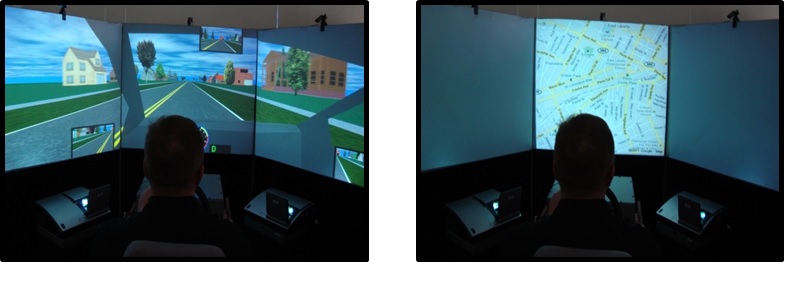

However, these existing studies did not specifically address the difference between the glance patterns of novice and experienced drivers. So in order to determine where these differences arise, the professor and his researchers tracked the distribution of eye glance duration for a cross section of drivers in a driving simulator. As they were ‘driving’ along simulated roads the drivers were asked to undertake tasks such as getting change from a centre console to pay a toll and adjust the car’s defroster setting. Researchers then measured the proportion of glances away from the road that lasted longer than two seconds.This revealed stark differences: 80.5% of novice drivers took their eyes off the road for 2.5 seconds or longer compared with only 5.5% of the experienced drivers. Indeed 30% of novice drivers glanced away from the road for five seconds or longer.

To address this issue, inexperienced drivers were given simulator-based concentration and attention training to teach them to keep in-vehicle glances to less than two seconds. “There is a debate about whether this teaches drivers that it is acceptable to look inside the car provided it is not for longer than two seconds. But if we tell them nothing then 80% will look inside for longer than two seconds and that is unacceptable,” said the professor.

He said by using a low-cost STI simulator with simple programming, this training could be made available through many organisations. To overcome the need for an eye tracker in order that the training programme was more widely available, drivers have to press a button to switch the view on the front screen of the driving simulator from the roadway to inside the car, and press again to restore the roadway view. They were given the task of using satellite navigation to ‘drive’ to a location while the time between the button presses was logged. Each session was videoed so if drivers switched away from the roadway view for too long, they could be shown the footage of their mistakes.

Value of experience

Half of the inexperienced drivers were given concentration and attention training while the other half received placebo training.While the 83% of the untrained drivers’ glances away from the road lasted for longer than two seconds, with trained drivers the figure was only 28%. At 2.5 seconds the proportions drop to 41% and 5% respectively and none of the trained drivers’ diverted their attention for longer than 2.5 seconds. However a quarter of untrained drivers’ glances lasted for longer than three seconds, 11% for longer than 3.5 seconds and 3% for longer than four seconds.

In a PC-based version of the training the road view appeared at the top of the screen and the map at the bottom. One half was blanked out at any one time and the driver clicked between the two. Without a steering wheel the virtual vehicle could not crash, so the trainee drivers were asked to identify hazards ahead and click on them using the mouse while periodically switching their attention to the GPS map to navigate to the destination. This enabled the system to measure the proportion of hazards the driver identifies and the duration of glances at the map.

Other studies done by Arbella Insurance using a simulator-based training program (Distractology 101) that was developed by UMass Amherst and delivered to high school students around the Commonwealth of Massachusetts compared the crash rates of young drivers in the year after they had been given distraction awareness training with their placebo-trained counterparts. The Arbella study found drivers who underwent distraction awareness training were involved in 24% fewer crashes. The results will be reported at an upcoming conference.

Hazard anticipation

The second factor the professor wanted to examine was hazard anticipation and in order to do so novice and experienced drivers drove a number of scenarios in UMass Amherst’s simulator while their eyes were tracked. One of these scenarios was a truck stopped in the parking lane just upstream of a midblock crosswalk – a situation similar to the one in which the student was killed. The truck obscured a pedestrian who might be stepping onto the crosswalk. The tests showed that most experienced drivers looked at the front edge of the truck to determine if a pedestrian was crossing the road.However, the novice drivers’ focus and attention remained on the lane directly ahead, so they may not have seen a pedestrian on the crosswalk emerging from behind the truck until it was too late to avoid a collision.

Only 10% of the inexperienced teen drivers glanced towards the front edge of the truck whereas with 30-year old drivers the figure was close to 30% and this increased to almost 60% with drivers over 60. “This shows a huge difference in the hazard anticipation skills of novice and experienced drivers,” said the professor. “And the better you are at anticipating hazards the less likely you are to crash.”

To teach novice drivers about what he calls latent hazards – hazards that could materialise but have not yet done so - the professor and his team then developed a risk awareness and perception training (RAPT) program. In the PC-accessible system, drivers were asked to drag symbols to areas where there could be hazards and indicate where they would be looking for those hazards. Again the results were dramatic: fewer than 10% of the novice drivers recognised some of the potential hazards while after training the score exceeded 90% for four of the nine scenarios. And once trained, at least half of the drivers recognised each of the potential hazards.

Transferring training

To check if drivers transferred this training to the road, RAPT-trained teen novice drivers and experienced drivers were tested in an actual car navigating a route in a town near the university that included highway, city and rural routes – along with a number of potential hazards. Novice untrained and novice RAPT-trained drivers were initially tested immediately after gaining their licence (and RAPT training) and both sets of drivers were tested again a year later. Experienced drivers were tested once. The results showed experienced drivers identified 80% of the hazards. By comparison, the untrained inexperienced drivers initially identified fewer than 50% of the potential hazards and that fell below 40% within a year.The RAPT-trained drivers initially identified around 65% of the potential hazards although a year later it had fallen back slightly but remained above 60%.

“What this shows is that in an hour you can get novice drivers halfway to the level of hazard anticipation of a driver with between 12 and 20 years of experience,” said the professor.

In a recent evaluation of a condensed version of RAPT by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, half of the 5,250 teens drivers in California were given an additional 17 minutes training immediately after they received their licenses.

All the participants’ crash records were gathered for the following year which showed that the trained males achieved a 23.7% reduction in crashes - although there was no significant difference in female crash rates. In the highest risk group, 17- and 18-year old male drivers, the comparison was even more dramatic with reductions of 43% and 35% respectively.

The professor said this was the first study ever to show the beneficial effect of driver education in crash reductions (the Arbella study followed shortly on the heels of the NHTSA study).

Life and death

Although experienced drivers have learned not to take lengthy glances away from the road, the professor and his team wanted to test if mobile phone use was a cognitive distraction every bit as dangerous as an in-vehicle distraction where the driver’s eyes are off the road. They set out to evaluate the effect mobile phone use has on experienced drivers’ hazard perception in an city setting using five of the simulated scenarios that were used by the novice drivers. Again the comparisons are startling. Despite these drivers being experienced, their hazard recognition in the hidden crosswalk test fell from an unimpaired baseline of more than 90% to around 20% when using a mobile phone.“When using a mobile phone the experienced driver cannot identify potential hazards any better than a novice, and if a potential threat materialises into a real one, the result will be the same.”

In concluding, the professor told his audience: “The last two seconds of your life could be those two seconds when you are looking down; you won’t have time to look back up because at that point the car in front of you will stop and you or that person won’t make it through the rest of the day. It’s that simple. You shouldn’t spend time looking down inside the car because you can’t tell when something you didn’t predict is going to happen.”