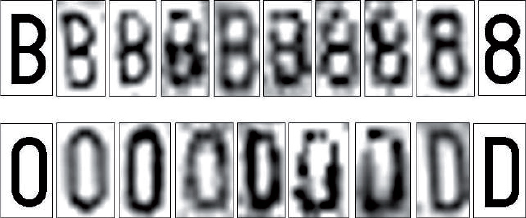

How 'noise' affects the recognition of characters and numbers, in this case 'B' and '8' and '0' and 'D'

EngiNe srl's patented Plate Matching technique is something of a paradox, in that it achieves formal vehicle identification without recognising, in the accepted sense, the characters on its number plate. Here, Angelo Dionisi of ENG Group explains how it works

We humans have a great tendency to anthropomorphise. We routinely discern human thoughts and emotions in the faces of other animals, mammalian or otherwise, and often credit machines and even inanimate objects with intelligence and personality. There are pragmatic, real-world consequences of this: automotive manufacturers, for instance, place great stock in customer focus groups' perceptions of the welcoming or neutral visage created by the lights and grille on the front of a motor car, and there are many other examples of where producers work to make their technical wares somehow more 'organic'.ITS is as prone to this phenomenon as anything else. And as systems capabilities and, in particular, computer processing power increase, the tendency is for manufacturers and suppliers to make greater reference to the ability of a new offering to think or act in a human fashion. Vision systems, for example, are frequently described as working "just like the human eye".

In the case of vision systems, however, anthropomorphisation perhaps makes better sense, as sight involves not just the eye but also an accompanying psychological process which governs perceptions.

It is something which Angelo Dionisi does quite readily when describing

Patented technique

The Plate Matching technique was patented in October 2008 and has been available in a production form since March last year. In essence, the EngiNe patent describes a solution designed to address the problem of visual 'noise', often encountered in images, which adversely affects number plate character and thus vehicle recognition. Figure 1 shows examples of this."Infrared [IR] is commonly used by system manufacturers as it is very good at cleaning unwanted information from images. Effectively it reduces that noise, so increasing the chances of a successful image capture and, if necessary, prosecution," Dionisi, who is head of R&D at ENG Group (of which EngiNe is part), explains. "But even so conventional IR-based OCR is far from foolproof. More advanced OCR solutions will attempt recognition by analysing a plate's format - referring to accepted combinations of numbers, letters and symbols, for instance. But how do you achieve a system which will work in all countries without specific reference to a given country's rules or formats? A complicating factor is that fonts can be an issue even within a single country - in India, to give just one example, there is no standardisation of fonts or character spacings and plates can literally be bought off stalls in markets. Attempting to force recognition of a given character on a plate is often unreliable even with the most sophisticated OCR systems."

Information content

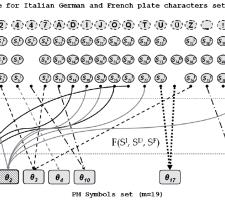

"Plate matching gets round that by recognition of information content rather than letters. So, for example: a '1' is defined as an empty character; a 'D' or a '0' has a hole; a 'B' or an '8' has two holes; a 'Z' is a zigzag, like a '2' or a '7'; an 'A' is an upward point like a '4'; and a 'V' is a downward point like a 'W'.

Figure 2 shows how this is done.

For average speed monitoring, a comparison (or ranking) function is applied to image captures from cameras sited along the stretch of road being monitored.

Dionisi: "Plate Matching's failure rate is only around one in 4,000. If there's any doubt, we simply don't issue a fine. But if that seems a rather hit-and-miss way of going about things, we achieve a far higher level of accuracy than is achieved with conventional OCR.

"This is because we're comparing a 'string' not simply a series of letters from a recognised alphabet. It's the same principle as the human eye uses to scan for something before focusing on a specific area," he adds, drawing on that anthropomorphic link.

Expanding further on how Plate Matching works, Dionisi describes it as the "synthesising or distilling of symbols rather than the positive 'forcing' of an identity onto a letter or number". The technique is, he says, something of a paradox in that it achieves recognition by comparison rather than through recognition in the true sense.

"The offset capabilities of Plate Matching are also very favourable when compared with those of OCR," he continues. "The technique's ability to achieve higher rates of recognition increase the Celeritas system's positioning flexibility. Mounting the camera at the roadside rather than on an overhead gantry reduces the maintenance burden and increases operatives' safety."

The Celeritas system

"Lots of people do image capture. The use of IR is common as it reduces image interference," says Dionisi. "But even by day that means having to have two cameras - a colour camera to provide contextual confirmation and another, IR camera for the number plate capture. For speed measurement applications, Celeritas, which is PC-based, needs only one camera per location to provide both contextual and number plate data." In common with many other enforcement solutions, Celeritas uses colour by day and IR by night. Operating at 25-30fps in digital mode over a visible area 35m long, the Celeritas system's fully HD (1,920 x 1,080 pixel) camera can cope with speeds of up to 350km/h. Speed analysis is based on analysis of multiple image captures (a vehicle's speed is established by measuring how far it has moved within a measured time within the camera's field of view) and EngiNe claims a margin of error of less than 1 per cent.

"We have a group policy of producing systems which do not have arguable margins of error," says Dionisi. "If there's any doubt, we won't prosecute. That's also a reason why we use colour images - they provide the maximum level of supporting identification." One camera can cover up to two lanes and by virtue of its use of image analysis the system is capable of overcoming a traditional speed enforcement problem: that of whether only one or more than one vehicle in an image is committing a speeding offence.

A typical average speed measurement solution will use up to four cameras to measure speeds between two points on a multi-lane road. Side or overhead mounting is possible (the offset distance for side-mounting can be up to one sixth of the viewed length) and in order to comply with Italian laws installations to date have been at a minimum height of 2.5m. Dionisi notes that there is no real maximum height, as the optical element of the camera is adjustable. Absolute speed performance is dependent on field of view.

In operation, the camera takes standard images and compensation for light levels is carried out within the system's software; Dionisi says that operations are unaffected during transition periods (dawn and dusk, for example) or inclement weather.

The use of image analysis also means that the camera itself is the trigger - there is no intrusion into the road surface - and he is keen to highlight this infrastructure independence which, he says, is a major differentiator between Celeritas and other manufacturers' systems.

Currently, the Celeritas system is deployed on motorways and national roads across Italy. Specific applications include one on the River Po, where it is used to monitor vehicles' speeds on a 19th Century iron bridge which is crumbling under the weight of modern traffic; other systems have recently been installed on the A21 in the Lombardia region, on roads in the Brescia area, and on the Centro Padane Motorway. Several others will be installed in the next few months.

In Italy, distribution is handled by another ENG Group company, ENG Techno, via a partnership with Finmeccanica; abroad it is accomplished under various joint ventures via other ENG Group companies.