"The cost of any country’s data collection is small compared with its total transport expenditures", Todd Litman

Todd Litman of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute in Canada makes the case for enlarged and improved transport-related data.

Comprehensive, high quality data is useful, or even essential, for many types of decision making and transport is no exception.Planners and researchers can cite countless situations where their understanding of transport problems and their ability to evaluate potential solutions is constrained by inadequate data.

Many authorities and other agencies collect basic data, such as the number and types of vehicles on the road, distances people travel, the amount of fuel consumed as well as deaths and injuries. But it is often difficult to determine and compare data from different jurisdictions or time periods. And now new planning issues are expanding the demands for transport-related data.

To be useful for planning and research, data must be suitably comprehensive, accurate, consistent, transparent, frequent and available. It must include multiple facilities, modes and impacts, at appropriate geographic scales (local, regional and national).

Various transport data programs exist and most local and regional authorities collect official statistics which national and international organisations integrate into multi-city and multi-country data sets suitable for comparison and analysis. However, national data program quality varies, particularly in developing countries. International organisations such as the

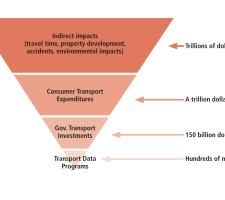

The cost of any country’s data collection is small compared with its total transport expenditures and the impact transport has on its economy. So even a modest increase in a transport system efficiency will represent large economic returns on data program funding. In America the annual expenditures on transport data programs are small compared with the many billions of dollars spent on transport facilities and services and the trillions that consumers spend on transportation. As a result, the costs of improving data quality can be repaid many times over if they provide even small increases in transport planning efficiency.

However, effective transport planning requires diverse, quality data which must be suitably comprehensive, accurate, consistent, transparent, frequent and available. And as improved transport data can result in more efficient and responsive planning, the savings and benefits that will follow will offset incremental program costs many times over.

Expanded data programs

To reduce costs many transport data programs are under pressure to collect only the essential or productive data needed to comply with current planning and performance evaluation requirements. But as we cannot predict which planning issues will become important, or what evaluation and research will be needed for future policy and planning, there is a good case for expanded and improved data programs. For instance a newer planning paradigm considers a wider set of modes including accessibility factors, objectives and impacts – all of which require additional data for evaluation and research.New planning issues are becoming important, such as encouraging walking and cycling for utilitarian and recreational travel, the affordability of transport for low-income households, as well as parking problems and traffic congestion. Taking these factors into consideration at the planning stage requires additional data to be made available. For instance conventional transport planning is often mobility-based and assumes ‘transportation’ primarily means motor vehicle travel. It therefore bases the evaluation of a transport system’s performance primarily on automobile travel conditions, such as average traffic speed, congestion delays and operating costs. This not only overlooks other modes and other accessibility factors, such as walking and cycling conditions and roadway connectivity, but also it does not take into account the density and mix of land use. More comprehensive, accessibility-based planning expands the range of impacts and options considered at the planning stage and this can lead to more efficient and equitable planning decisions.

In order to allow comprehensive, accessibility-based planning decision makers require data on the quality of travel by various modes including supply and quality of sidewalks, crosswalks, public transit supply, transit comfort and speed, bike lanes and road and path connectivity. This is in addition to existing data on vehicle traffic speeds and land use density and mix.

Congestion has long been a significant urban transport problem and the conventional solution is to expand roadways. This is not only costly, it also creates additional barriers to pedestrian travel and exacerbates other transport problems by encouraging additional vehicle travel and stimulating urban sprawl. Many communities are now considering alternative congestion reduction strategies such as more efficient road and parking pricing, more accessible land use development, more connected road networks and improved user information on travel conditions and options. As conventional planning measures congestion by the reduction in traffic speeds, it would not evaluate the reduction in delays realised when people switch to alternative modes of transport or from changes in land use that reduce trip distances.

Evaluating alternative congestion reduction strategies requires measuring existing traffic congestion problems and modelling the congestion reducing impacts of changes to alternative modes of transport, mode shifts by commuters, pricing reforms and changes in roadway connectivity. To do this data must not only be collected on vehicle traffic speeds and delays, but also on per capita travel times and congestion delays, along with the effects of pricing and roadway network traffic.

Automobile-orientated | Multimodal | Sustainability | |

|---|---|---|---|

| | Vehicle travel demand, roadway conditions, traffic speeds, level of service, accident rates | Demand for alternative modes, quality of non-motorised and public transport service, land use accessibility | Various social and economic impacts including travel affordability, quality of access for non-drivers, health etc |

| Comprehensive | Good within U.S. transport agencies. Moderate to poor at local and regional levels | Incomplete. Starting to improve for multi-modal level-of-service evaluation | Incomplete. Some data are starting to improve, but others not at all |

| Accurate | Good | Generally poor | Mixed, but generally poor |

| Consistent | Good consistency between states. Moderate to poor at local and regional levels. Little consistency with other countries | Generally poor | Generally poor |

| Transparent | Moderate to good | Generally poor | Generally poor |

| Frequent | Moderate and declining | Generally poor | Generally poor |

| Available | Moderate to good | Generally poor | Generally poor |

Availability and improvements

Most communities have good data on roadway facilities and conditions and some transit service factors (coverage, frequency, speed, reliability and sometimes crowding). But few have all the data needed to evaluate non-motorised transport services, or for efficiently evaluating roadway network connectivity and land use accessibility. This can include the increased number of services and jobs accessible to local residents from a change in pathway or roadway design, transit service supply or land use development patterns.Only a few current data models can effectively evaluate the full impacts of roadway expansion as they tend to underestimate the generated and induced travel effects and the resultant incremental costs. Nor do they evaluate the full benefits of improving alternative modes of transport, of more efficient pricing or increased roadway connectivity. This requires detailed data on traffic conditions (travel speeds and delays) and transport demand and activity (how much people will travel under various conditions and prices). It must also include information on mode shifting that will result from changes in the quality of alternative transport systems, prices and roadway networks.

To carry out comprehensive, accessibility-based planning requires an integrated set of transport and land use data as described above. As some of that information is already collected, data quality can often be improved with incremental expansion and improvements to existing data programs.

In the US, the current data program development efforts may be adequate for improving the ability of transport agencies to model and evaluate motor vehicle travel conditions. However, they will be inadequate for evaluating other modes and accessibility factors or other types of impacts, and will be least adequate for research purposes. As a result, future research will be less effective and more costly than if we start now to expand and improve data programs.

This is not to single out the US, as data program strategic development plans in other countries are even worse in this respect.

There is a need for transportation professionals and their representative organisations across the globe to communicate the value of high quality data and to support more strategic data program planning and development. Relatively simple actions, such as standardising definitions and collection methods or eliminating duplicated data collection by various agencies, can improve quality while reducing costs.

There is a need for professional organisations to support strategic data program developments. This should include national organisations to support domestic data programs with international organisations providing guidance and coordination among various jurisdictions and agencies.

We must become articulate at explaining the various benefits provided by data, the risks of reduced data quality and the economic returns provided by data program investments. This must include detailed technical analyses and easy-to-understand examples that communicate these concepts to general audiences.