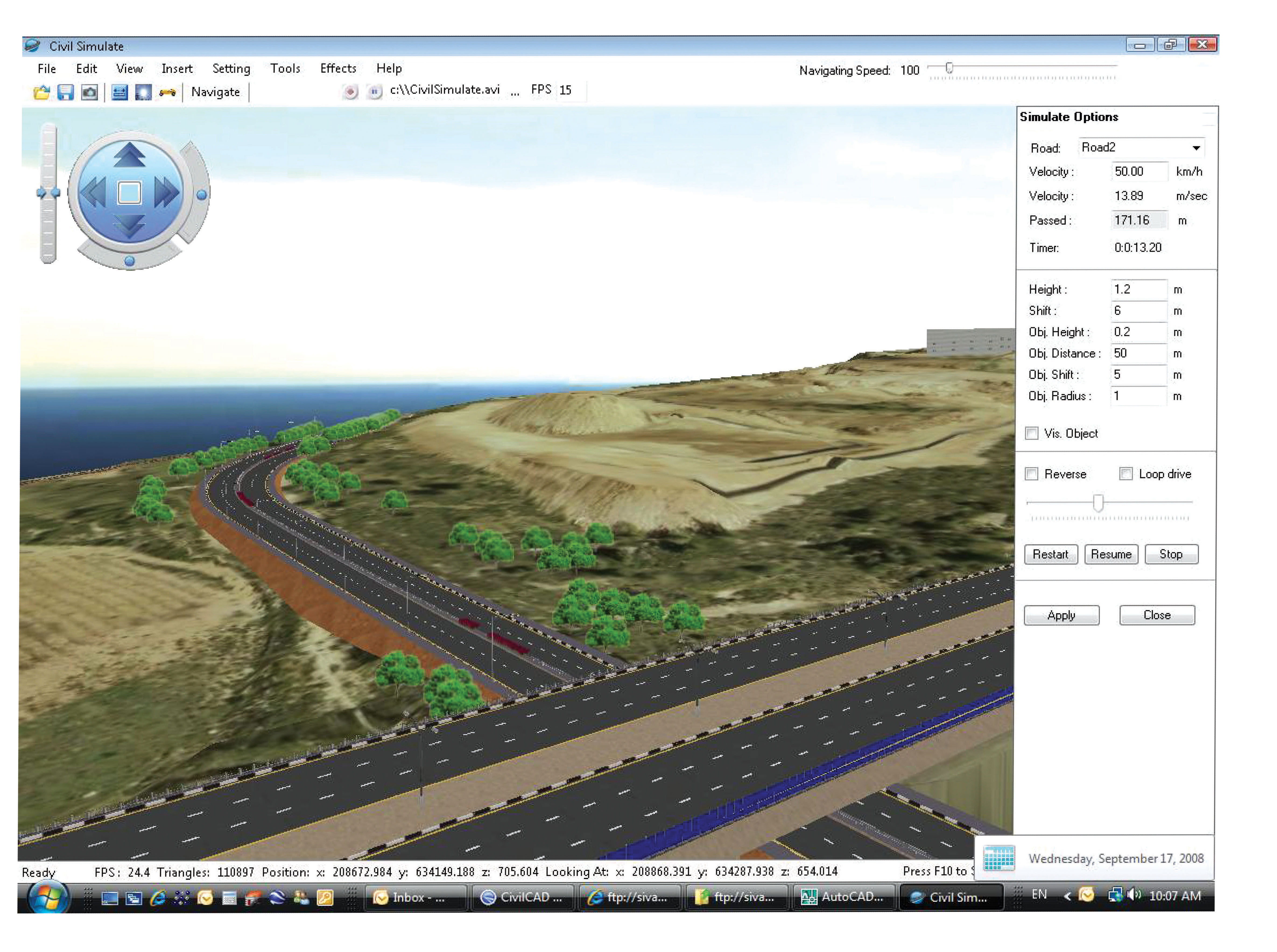

Using Sivan's package, a customer can create virtual reality impressions of complex structures

Adrian Greeman looks at developments in software visualisation packages

The capacity to make visualisations has been growing in importance over the last decade, and is now a well-accepted part of consultations and client presentations. But making high-quality images of projects is still a major undertaking and larger consultancies employ specialist departments to do so. Costs are coming down but it can still take a while, and some high-capacity hardware, to produce realistic renderings from drawings and 3D models, usually merged with photographic overlays on surfaces and advanced lighting effects.

Various products are coming onto the market which ease the task and speed up the processes, in many cases allowing the engineer or technician to produce satisfactory images.

High-grade representations still require specialist work in tools like

But there are various new products appearing which can do medium-level representations well. The basic 3D CAD tools themselves have ever-increasing rendering and image-producing capacities, both in AutoCAD and products built on top of it like Map 3D and Civil 3D, and in

"It used to be the case that you needed a parallel workflow - taking the model information into a separate program, but this is now unnecessary," he says.

The tools can be used easily by an engineer, he adds, to quickly produce a rendered version of the design: "It is the fastest rendering I have ever seen and does the more complex things like adding a changing quality of light as well as direction for dawn or evening representations." That means it is useful not only for client and inquiry presentations at the end of design but as a checking and design tool in itself, constantly allowing a to-and-fro by the design team to improve its design understanding.

Croser argues that the embedded tools have sufficient capacity to eliminate the need for external products and parallel work flows. But for those who still see advantages in specialist tools, and particularly the 3d Max visualisation and rendering tool which is part of the AutoDesk portfolio, there are other ways of simplifying the tasks.

One in particular is the Dynamite programme produced by the independent British firm

It does two things, explains Director and company owner Bruce Harfield: "Firstly it connects directly with the models in the design software, drawing in and reading what the various components are".

For MX this is done directly whereas for Civil 3D the underlying model is complex and requires some 'translation'. The AutoDesk DWG file is changed to a special Dynamite file with data that is not required for the visualisation tool stripped out.

Harfield believes Civil 3D to be an increasingly important product and has worked closely with AutoDesk on the translator which sits within Civil 3D itself.

"It matches the names which define assemblies and components in Civil 3D to elements in Dynamite, automatically applying the right textures and materials," he continues.

Automatic texturing is also done from MX but requires a disciplined naming convention to be maintained by the engineers building their model, because Dynamite uses specific names for recognition.

With this information the program then builds in 3D Max. "Max is a complex program that takes a lot of time to learn properly," says Harfield. "It is very powerful and has high-quality rendering, is efficient and allows you to do animations of elements inside as well as 'helicopter' or 'car' traverses.

"But the program needs you to work from first principles - shapes like basic cubes and cones are available but nothing that is immediately usable by an engineer, and especially for roads." One of Dynamite's major functions has been to create a library of objects suitable for road visualisation, like lampposts, road markings, signs and vehicles. These are parametric, which means their heights, length, colour and speed can be specified, allowing for thousands of variations.

Some of these are applied automatically and the user can specify how that happens using a variety of wizard tools. Users can also set up 'styles' with a particular set of parameters so that they can easily reproduce, for example, UK motorway standards or Finnish country roads.

The program sits inside 3D Max, which must also be installed to operate. Data however can be exported from a different computer with the design software and simply drawn in.The result is a much easier version of 3D Max that requires only one or two days' training according to Harfield. Engineers can then quickly produce a high-quality rendering which allows a new version to be produced each time the design is changed, for design assessment and communication with clients and others. An alert tells the user of changes in the underlying model and the visualisation can be updated automatically.

The company is increasing the number of objects in its library and some resellers abroad also add locally specific items.

These now include North America via the Canadian software specialist

A version of the program has also been released for tying into the Vissim traffic microsimulation programme from PTV, and a version suitable for SIAS Paramics is also being developed.

But there are other visualisation possibilities too, perhaps at lower cost overall, or for those without access to the higher-end starting tools. Israeli CAD tool software producer

Sivan says that it can give accurate virtual reality vision of complex structures such as junctions, roundabouts, parking lots, interchanges, ramps, bridges and tunnels.

Interactive drive-through or aerial views are possible and under different settings such as fog, snow or night driving. A distance measurement capability allows for visibility safety checks. Accuracy is high to plus or minus 20mm to the CAD model, and the program will handle large-scale projects.

Finally there is the virtual modelling capacity of