Traffic management has largely been shielded from the sort of malicious hacking that is commonplace in other industries – but with billions of connected devices in the world it won’t stay that way, warn internet experts Keith Golden and Brandon Johnson.

Traditionally isolated from networks and the internet over most of its history, the traffic management industry has largely been shielded from malicious hacking and system intrusion that have become commonplace in other industries. However, as the rate of connected and autonomous vehicle technologies marches ahead, the appliances, sensors, components, and machines related to vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) and vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) systems (V2X) represent new attack surfaces, clearly placing the traffic management industry front and centre in the cybersecurity discussion.

Other industries have confronted this threat from the very beginning, including the IT industry. As a result, the ITS and traffic management sector can learn valuable lessons and avoid many pitfalls.

What’s at risk?

The last two decades have seen a sharp resurgence in ITS technology development and adoption, particularly at the intersection. These new technologies, especially connected systems and devices, are spawning new solutions to roadway efficiencies and capacities, while ushering in the connected and autonomous vehicle (CAV) world.

Fortunately, there are safety measures (conflict monitors or malfunction management units) built into traffic control cabinet systems that will set the intersection to a safe, flash mode should a hacker break into a traffic controller and attempt to make an unsafe change to the database (such as conflicting movements or setting clearance timing below safe minimums). While there’s no chance for an all-green or all-yellow intersection, even changing traffic signal timing of a controller is not acceptable.

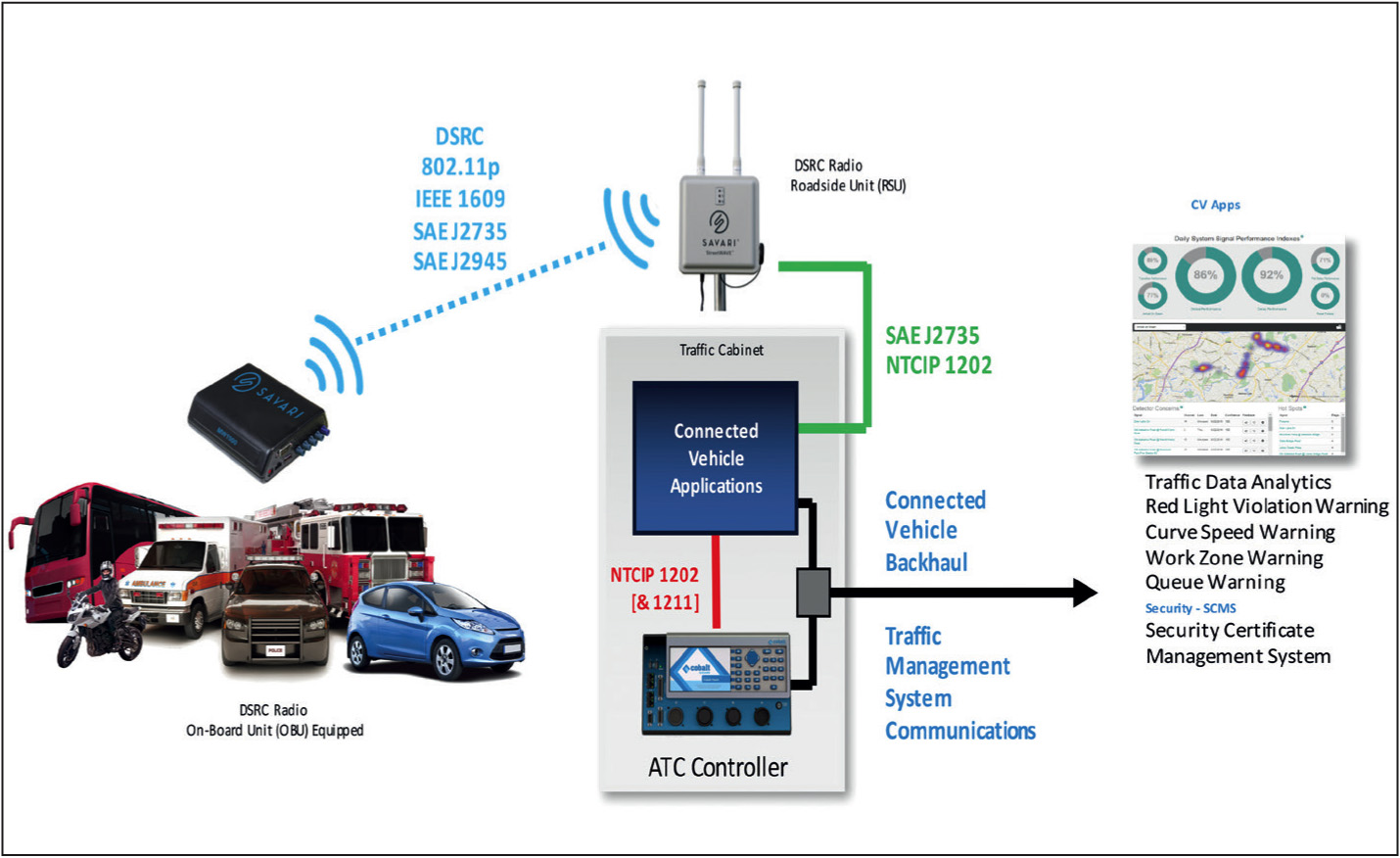

It is imperative that we (the transportation industry, agencies, manufacturers and so on) are collectively supporting existing cybersecurity initiatives as all of them impact the security at the intersection. This includes support of SPaT (Signal Phase and Timing) and MAP or geometric intersection description (GID), and other CAV wireless messages that are critical to the CAV environment.

Connected vehicles

Today’s vehicles already have the computing power of several personal computers and process gigabytes’ worth of data. While most of this computing power has traditionally focused on optimising the vehicle’s operability and internal functions, more and more of this technology is now being focused on the vehicle’s ability to connect externally: V2V and V2I. These technologies have proven the capability of dedicated short range communications (DSRC) in infrastructure applications. However, this adds a new vulnerability to the equation.

Connected vehicles are particularly vulnerable due to the number of attack surfaces present in each vehicle, including cellular, Bluetooth, WiFi, satellite radio, etc. The advent of V2V and V2X adds more attack surfaces to a vehicle. This means the threat to connected vehicles from a cyberattack is very real, and the threat will only increase in the future as the level of connectivity expands. Recent hacks to vehicle remote mobile apps demonstrate this vulnerability.

Protecting today’s vehicles from cyberattacks is the focus of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and standards by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) to address cyber vulnerabilities in vehicles.

Lessons learned

Instead of reacting to breaches or responding to cyberattacks, it is incumbent on us all to stay ahead of the cyber threat and pay close attention to the best practices of the IT industry, which has been locked in an ongoing battle with anyone and everyone looking to exploit network weaknesses. Fortunately, the lessons learned in this domain and from others can be applied to the challenges faced by modern, interconnected digital systems such as V2X.

More important than any particular lesson is the mindset that means most IT professionals view the situation as a continuous battle where they are on the front line. It’s critical to understand that cyber threats are, in fact, asymmetric warfare, where the enemy’s advantage comes from the ability to create disproportionate effects from a single vulnerability, yet IT professionals have to protect vast and numerous attack surfaces. Mitigating these threats, we have to recognise there are particular IT principles that should be applied to designing, building, fielding, and maintaining V2X systems.

Security culture

In 1997, a coalition of transportation and standard development organizations, working with the federal government, established the National Transportation Communications for ITS Protocol (NTCIP) to ensure the interoperability of traffic equipment. A family of open standards that defines how transportation management systems communicate with each other, NTCIP became the ‘de facto’ solution to enable interoperability and interchangeability. However, it is time to change this approach to include cybersecurity at the intersection.

Under NTCIP overall communications network security was intended to be the responsibility of the design and implementation of field communications networks, or the technicians and engineers installing the communications components. For years, most other traffic control and management components and systems manufacturers have delivered products with username and password-protected security (that is often not used or left with defaults at the time of installation). But component-level security is no longer enough. The NTCIP standards leave a potential entry point for cyber attackers who can get past the security measures built into the communications network. This represents the first line of defence against a breach or an all-out attack: it is time to alter course to keep transportation management systems secure.

Moving forward

Providing improved physical and communications security should be paramount in the traffic management industry going forward. To do this, a re-examination of the cybersecurity vulnerabilities of traffic management systems, and the updating of our industry standards will be needed.Providing password-protected security on traffic control and system products is the first step. NTCIP was designed to interoperate among various network security methodologies - however, leaving the responsibility of network protection to the design and implementation of the field networks can no longer be a standard practice going forward. That is the type of vulnerability hackers could - and do - exploit.

Cybersecurity: best practices and policies

Design with security in mind, and think like a hacker. Ask yourself: ‘How could I compromise or break the confidentiality, integrity, authentication, or availability of this system?’

Secure coding practices

• No hardcoded passwords

• No admin backdoors

• Limit passing unencrypted information across a network

• Create segmented networks and systems that limit potential for lateral movement

Testing

• Test systems, not just components (sometimes called system-of-systems testing)

• Harden by attacking, refactoring, and attacking again to find vulnerabilities

• Test third-party components and software that are part of the system

Look at every link in the system, starting with people. Can they be convinced to give unauthorised access to a system or perhaps perform an unwanted action? How about the security of a connected system, workstation or laptop? It’s often easier to hack the connected device than to tackle the hardened components embedded in V2X systems. If that gets hacked, can credentials be gained and can the system be compromised?

Operational security

• Role-based access control – limit everything except what is expressly permitted

• Two-factor authentication wherever possible

• Open security models that can be peer-evaluated and reviewed (no security through obscurity)

• Patch and update as soon as vulnerabilities are discovered

• Prepare an incident recovery plan