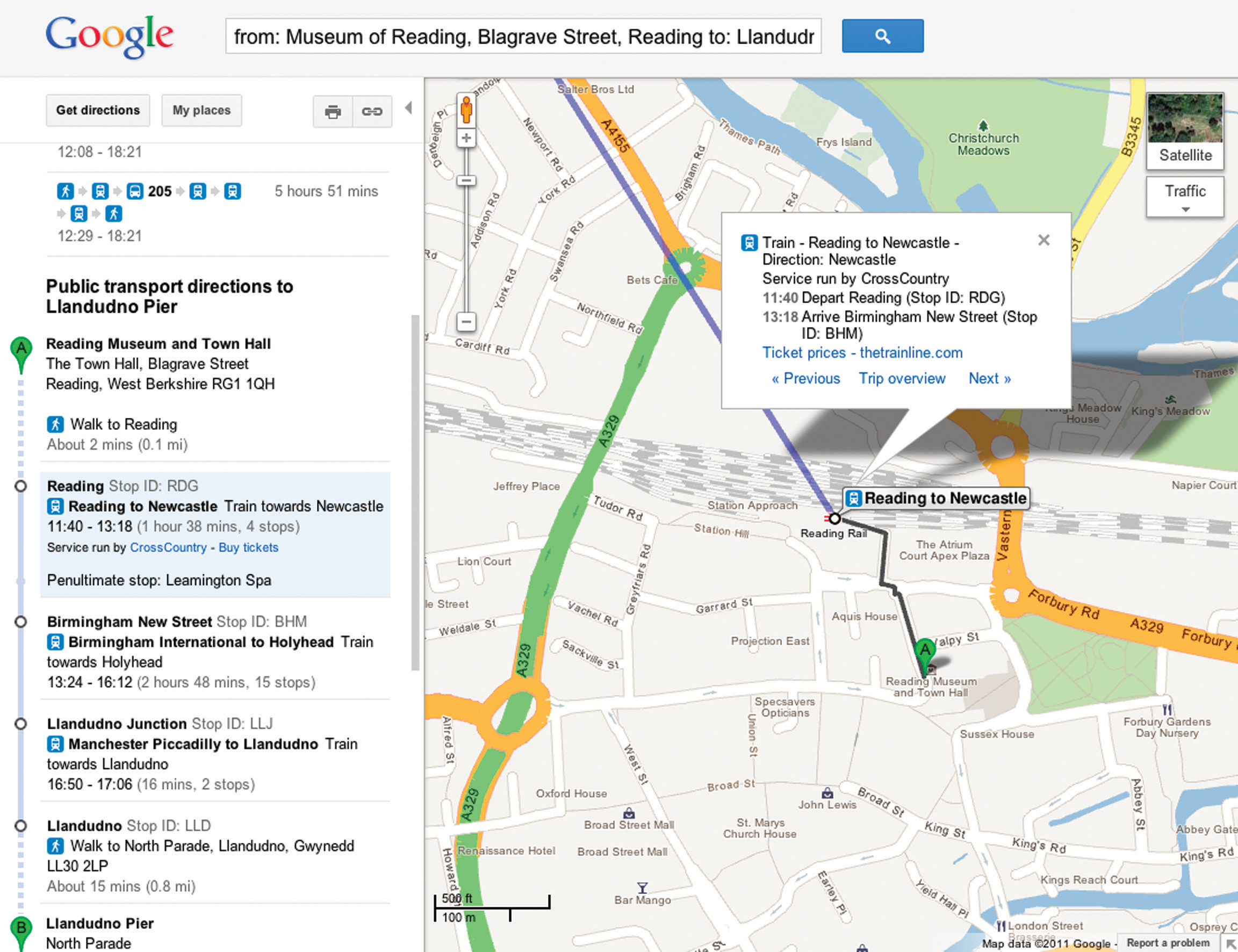

Google Transit – proof that transport information represents significant income generation for Google

Will the relentless growth of Google lead to it becoming the ultimate provider of travel information services? Huw Williams investigates Google’s strategy and David Crawford discovers what two principal rivals are doing to keep pace

In the first weeks of 2012 one company staked two divergent claims on the future of transport. One is the science fiction of only a decade ago, turned into reality: the driverless car. The other seems more prosaic, yet in its own way is just as significant a marker of the future, a national rail transport information tool that allows mobile users to access timetable information, purchase tickets and find the nearest station. These are just two of many ways thatTo understand Google’s strength, follow this path: Google’s core business is making money out of advertisements that are linked to online information searches. Google Maps is now the predominant location-based search tool.

During the 2011 Christmas weekend alone, more than three million Android devices were activated. Each device that uses Android comes bundled with a high specification version of Google Maps, including a free turn-by-turn GPS navigation system. This is functionally far more straight out of the box than the app Google provides on iPhones, Blackberrys and devices using their own operating systems. As Benedict Evans, an analyst of mobile and digital platform business at Enders Analysis points out, this has a cyclical benefit: transport information improves Google maps and helps promote Android which then further boosts Google Map’s supremacy.

“Google Maps is now at the core of location searching. Transport (information) is a way of making Google Maps better, increasing its lead over any competing service, to make it more likely that you will use Google Maps to do a location type search,” Evans says.

The recent UK launch of the Google Transit train information service is one of the latest improvements. This is the result of a link-up between Google and ‘thetrainline.com’; Google Transit being a new map-based user interface for thetrainline service, providing information on a potential 170,000 different rail journey options from 2500 stations across the country. Yet this is just one example of how Google Maps is integrating public sector transport information. Its Transit Navigation features are now available within maps of 440 regions in 50 countries, with more cities lined up for inclusion. The coverage of London, for example, helps guide mobile users, on foot or in cars, to tube and train stations, provides timetable information, and can even tell you when to get off the bus or tube so you are at the nearest stop to your destination. It includes 8,000 bus stops and 250 underground stations. For Evans, this is not simply a philanthropic app to help you move around more efficiently, it is further proof that transport is a significant income generator for Google.

“You will run a journey search and you will buy that train ticket and maybe a hotel room at your destination from an advert on the results page. Google will make money off that ad.”

If the public transport sector offers a ready means of income generation, it is road transport that provides Google with the potential for market domination and this is where Android’s importance becomes clear. In 2003, Google purchased a small California-based software company, Android Inc, and continued developing its smartphone operating system. Google’s next cunning move was to release Android as open source software to stimulate development of supporting apps. Finally, it provided Android as the operating system for the ‘Open Handset Alliance’, a loose group of mobile phone hardware manufacturers, established ostensibly to create industry standards for the smartphone industry, but arguably, also as a force to challenge the dominance of Apple’s iPhone. The strategy has worked: even on an average day, there are around 700,000 activations of Android devices. All of these come bundled with a free version of Google Maps that includes ‘Navigation’, its own free voice-activated, turn-by-turn driving and walking GPS system.

In-vehicle GPS navigation systems have conventionally required a dedicated hardware device. With GPS enabled smartphones, relatively modest purchase of a dash-mounted cradle and downloading of an app and the phone becomes a nav system. Companies such as

For Google, its push for traffic software dominance is backed up with user features culled from other Google resources; live traffic data updates; and also a satellite view familiar to Google Maps or Earth users to help drivers visualise their route. It also calls on Street View to show pictures of junctions where turns are to be made to minimise driver confusion.

Currently, Google buys its real time information. However, as more people use smartphones with Google Maps for turn-by-turn navigation, Google might well become the predominant source of user-mined traffic data, a rapidly growing and potentialy huge business.

Yet, seemingly well aside from all of its core involvement with mapping services, Google has just been granted a US patent for the driverless car. The patent relates to how the car will know when to switch between automated and human control, where it is located and the direction to drive. The burning question is though, why does Google want people to have driverless cars? David Levinson, chair in transportation engineering at the

“If you are spending an hour a day driving a car you that’s an hour you can’t be surfing the internet or using Google services. If you are travelling alone you might as well be surfing the net, if the car can drive itself. The potential to capture people for an extra hour a day is enormous.”

And if you are in your car, surfing the net, location-based services are likely to be what you are searching for. It is a short step from a robot car project back to Google’s core business: mapping. But is this really just a glamour project? A diversion for a company with more money than it knows what to do with? Possibly not. David Levinson believes that even though Google might not become a vehicle manufacturer, its innovation has accelerated deployment of automated vehicles by at least 10 years. Interestingly, by framing the patent as they have, it doesn’t lock companies out of developing similar technology. As Levinson explains, if robot cars do become a reality there is a further implication for Google’s business.

“You can’t use the driverless car unless you have a complete and accurate map of the transport network, but

linked to that the driverless car can also be used to make that map more microscopically detailed, where road markings are, where the curb is, what other objects there are in the road, what the signal phasing is. So a Google autonomous vehicle is not just a driverless car, but also a probe to help it map the world in more detail.”

It seems that it in the end it all comes back to maps, but is there a Google plan for transport information domination? Levinson is unconvinced:

“I think Google’s strategy until quite recently at least was to throw a lot of things against the wall and see what stuck. It has an autonomous vehicles policy that will feed back to mapping ultimately, and a mapping strategy that is to map the world in detail and real time. But I don’t know if there is a single master plan”

For Benedict Evans the situation is even more simplistic, Google is all about searches and anything that comes within that sphere is fair game, though transport like all other potential sources of income will be hunted tirelessly.

“The fundamental priorities for Google at the moment are mobile and location services and transport is obviously a very important part of that. Google Maps will suck in all location specific data it can possibly get its hands on so that Google is the best place to find that information.”

Google’s History

1995: Larry Page and Sergey Brin meet at Stanford University.

1996: Page and Brin begin collaborating on a search engine called BackRub.

1997: BackRub is renamed Google – a play on the word ‘googol’, a mathematical term for the number represented by the numeral 1 followed by 100 zeros, reflecting their mission to organise the seemingly infinite amount of information on the web.

1998: PC Magazine lists Google as the preferred search engine in the Top 100 Websites for 1998.

2000: Google is released in French, German, Italian, Swedish, Finnish, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Norwegian and Danish – Google becomes the world’s largest search engine.

2003: Google voted “The Most Useful Word of the Year” by the American Dialect Society.

2004: Google Local is launched, providing neighbourhood business listings, maps and directions. (Local is later combined with Google Maps).

Google’s first public listing takes place on Wall Street with an opening price of USD85 per share.

2005: Google Maps and Google Earth go live.

Google Transit is launched allowing people in Portland, Oregon, USA metro area to plan their public transport trips.

Traffic information is made available on Google Maps for more than 30 cities around the US.

2007: Street View launched.

Google announces RechargeIT, its investment in accelerating the adoption of plug-in, hybrid electric vehicles.

Android and the Open Handset Alliance are announced.

2008: Maps for Mobile launched giving public transport directions on mobile phones in more than 50 cities worldwide.

2009: Google Maps Navigation, a turn-by-turn GPS navigation system, launched.

2010: Cycling directions and cycle trail data added to Google Maps.

Experimental self-driving car technology logs more than 140,000 miles.

2011: Google Maps Navigation updated to route users around traffic congestion.