Swedish capital Stockholm is implementing an experimental air quality measurement system which aims to nudge people towards less polluting behaviour.

The mobile air quality sensor network, called Open-seneca, was one of the winners of the Women4Climate Tech Challenge 2020.

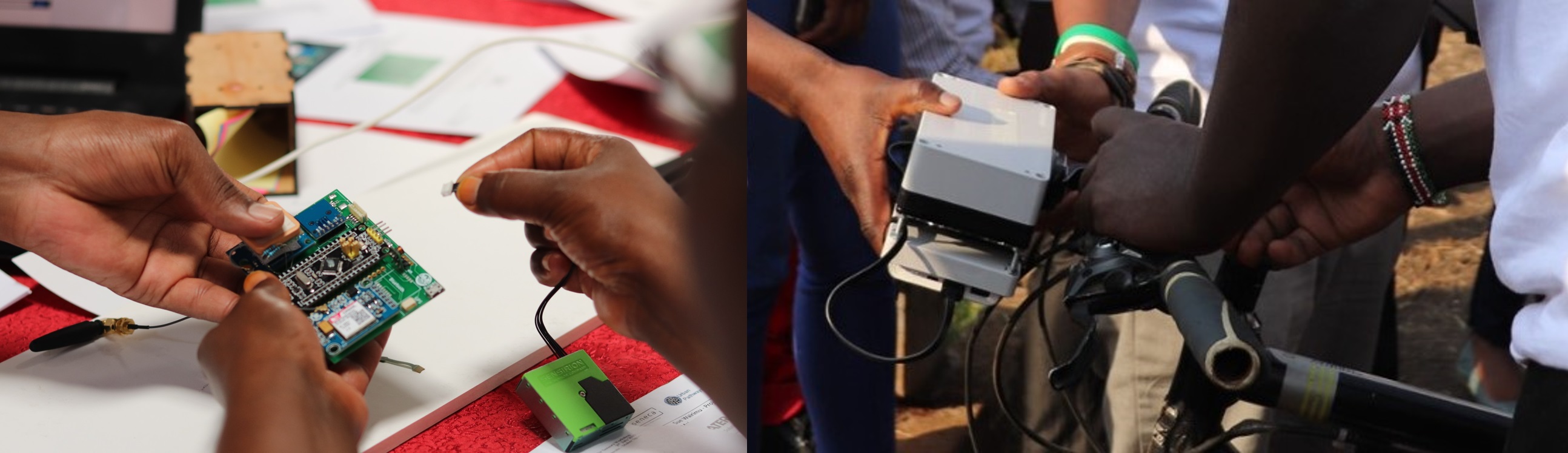

Lorena Gordillo Dagallier, a PhD student from the University of Cambridge, UK, came up with the idea of ‘citizen scientists’ using relatively cheap, small monitors – which fit into backpacks or can be carried on bicycles - to record air quality data.

The main aim is awareness-raising, with communities able to pinpoint exposure to particulates and create pollution maps which will guide policymakers and planners.

“It's small enough so citizens can actually carry it around while they commute in their daily lives and map pollution,” Dagallier says.

“When people carry a sensor, they get to see their personal exposure, and that can induce behaviour change. And when we have enough people moving, we can map the whole city with a level of detail - a street-to-street level - that can provide information about where the hotspots would be.”

The hope then is that a link can be made. “We get citizens to think as well about the data and solutions,” she goes on.

“And, and once they identify something that we can do during daily life, or they can just improve their quality in a specific hotspot, we can make sure that that gets replicated at the city level as well.”

The sensor is relatively cheap, using off-the-shelf components. “The limiting factor is the particulate matter sensor,” says Dagallier. The sensors have GPS, and a battery which she would like to be able to reduce in size: “It’s quite big.”

They can be left in a fixed location. “But we find it's more useful, these sensors can provide more information, when they are moving around,” Dagallier points out.

Back office functions are straightforward: there is a Bluetooth module on the sensor that can communicate to an app on the user's smartphone.

There is also an SD card so people can manually take the card out and put it in a computer to get the data, and the sensor can transmit data directly to the Open-seneca platform without the need for a phone.

“The whole sensor is designed to be modular, depending on the needs,” she continues. “We give access to all of that to the local authorities we work with. The data would be accessible in case the authorities want to do much more than what we offer in our platform.”

The solution will be employed in Portugal’s capital Lisbon and it has piqued the interest of Stockholm mayor Anna König Jerlmyr, too.

She said: “By gamifying air quality measurement and pairing it to bike commuting, we are confident that Open-seneca has the potential to increase the wellbeing of our citizens.”

In an interview with ITS International, she went on: "We strongly believe that involving citizens can help raise awareness on the impact of air quality and the need to rethink the design and mobility modes in our cities.”

Politicians have a tough job: if you invest in bicycle lanes you can irritate car drivers; if you regulate on air quality it can seem as though you are imposing on taxpayers from on high with no understanding of what’s happening on the ground.

However, if you make people into ‘co-creators’ it might be a different matter, says Jerlmyr; to engage, to create a “code of citizenship”.

“When they get access to true data through sensors, and they can actually, in real time, measure air quality, then there will be a demand from the citizen themselves: ‘You have to do something about the air quality’,” she thinks.

The initiative will also bring more data into play. “Mapping the city means we know where the hotspot is, we can do something about it,” Jerlmyr adds.

This means it is more than simply measuring air quality on a few streets. “Now we can measure so much more,” she continues.

“This is just the beginning: this is information that we can use to just make better solutions for our citizens.”

For many people, for example, cycling is a more attractive option than mass transit in a time of pandemic; but with Open-seneca they should also be able to see clearly that cycling makes environmental sense.

Appealing directly to individuals, and creating a feedback loop with Open-seneca, is attractive, says Jerlmyr.

“You can actually ask a citizen and when you use the sensor, you can get feedback: How much is your carbon footprint? Or how is the air pollution in your area? Then you are informed - and informed citizens are good because they will also push for reforms or for transformations - so I think just that individual perspective is really important. So it will be citizen-driven.”

This suggests that, as with so many things in politics, motivation for change is actually going to come from the people themselves.

But at present most people, Dagallier thinks, do not see air pollution as a personal issue.

“I used to be one of them,” she concludes. “But now I am aware, and I want to raise awareness around me. With Open-seneca, I am committed to drive behavioural change and bridge the step between individuals and cities to build a healthier and greener future."

The Women4Climate Tech Challenge 2020 is a joint initiative from C40 Cities and the Velux Group.

This is a longer version of the article which appears in ITS International November-December 2021 under the headline Putting pollution on the map